In the previous post we encountered social security pioneer Eveline Mabel Burns née Richardson at the point in her career when the Columbia University economics department signaled a definitive end to any hopes for promotion from the rank of lecturer to a tenure track assistant professorship in economics for her with them. In this post we follow the parallel case of her economist husband, Arthur Robert Burns (and no, not the Arthur F. Burns of Burns-Mitchell fame!), who cleared the promotion to assistant professor hurdle at Columbia relatively easily, but was stuck at that rank for nine years, in spite of repeated proposals by the department to promote him sooner.

The heart of this post can be found in the exchange between the Arthur Robert Burns and then economics department head R. M. Haig in November 1941. Biographical and career backstories for Arthur R. Burns through 1945 can be found in excerpts posted below from budgetary proposals submitted by the economics department over the years. Burns was seen as a pillar of Columbia University’s Industrial Organization field at that time and remained at Columbia through his retirement (ca. 1965) while his wife took up a professorship in Social Work.

____________________________

From: Seligman’s 1929-30 budget recommendation to President Butler (December 1, 1928)

“During [Clara Eliot’s] absence [from Barnard College) Mr. A. R. Burns has been acting as substitute. In our judgment he has been a valuable addition to the staff, and we recommend that he be reappointed as instructor. In Miss Eliot’s absence the course in statistics has been reduced from two semesters to one. There is a distinct demand for an additional course, though it would be on a different basis from formerly, and our proposal is that Miss Eliot be appointed solely to give two three-point courses in statistics, conducting a statistical laboratory as part of this work. This would relieve Mr. Burns from the course in statistics, and enable him to offer a new course of a somewhat more theoretical character than any now given at Barnard, on “the price-system and the organization of society”, a course which would distinctly help to round out the present offerings in Economics”.

Source: Columbia University Libraries, Manuscript Collections. Department of Economics Collection, Box 3 “Budget, 1915-1946/1947”, Folder “Department of Economics Budgets, 1915-1934 (a few minor gaps)”.

____________________________

Biographical and professional background through 1930-31

of Arthur R. Burns

…Arthur R. Burns was born in London, in 1895. He served in the army from September, 1914, to April, 1917, when he was discharged as no longer fit because of wounds. He entered the London School of Economics at once, took his B.Sc. degree with honors in 1920, taught economics in King’s College for women (University of London) for four years, and took his doctor’s degree in 1926. The award of Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial Fellowships brought Dr. Burns and his wife to this country, where they traveled somewhat widely for two years, studied competitive conditions in industries characterized by large business units, and where they were induced to stay by Columbia.

Dr. Burns has now been a lecturer in economics at Barnard College for three years. Members of our department have thus had an opportunity to become well acquainted with his quality. We think that he is by native ability, temperament and training an investigator, and that, given such opportunities as the graduate department affords, he will make significant contributions to economic science. His publications include several technical papers and two books: Money and Monetary Policy in Early Times, 1926, (a learned treatise on the origin and early history of coinage and monetary practices), and The Economic World, 1927 (written in collaboration with Mrs. Burns).

Source: Letter outlining plans for the future development of the economics department by Wesley C. Mitchell to President Butler. January 16, 1931. In Columbia University Archives. Central Files 1890-, Box 667, Folder 34 “Mitchell, Wesley Clair, 10/1930 – 6/1931”. Carbon copy also in Department of Economics Collection, Box 3 “Budget, 1915-1946/1947”, Folder “Department of Economics Budgets, 1915-1934 (a few minor gaps)”.

____________________________

Department recommends promotion to Associate Professorship

already in 1937-38

[Note: actual promotion only occurred Apr. 3, 1944]

[…] I would make the following budgetary recommendations for the coming academic year [1937-1938]:

(1) That the salary of Assistant Professor Arthur R. Burns be advanced from $3,600 to $4,000. In the opinion of his colleagues Mr. Burns is an indispensable member of our group whose scholarly competence and accomplishments entitle him to recognition far beyond that yet accorded him by the University. At the earliest possible moment he should be advanced to an Associate Professorship.”

[…]

Source: Columbia University Libraries, Manuscript Collections. Department of Economics Collection, Box 3 “Budget, 1915-1946/1947”, Folder “Economics Budget, 1937-1938”.

____________________________

Department again recommends promotion to Associate Professorship

[Note: Burns was given the salary increase this time]

[…] I would respectfully make the following budgetary recommendations for the coming academic year [1938-1939]:

(1) That the salary of Assistant Professor Arthur R. Burns be advanced from $3,600 to $4,000. In the opinion of his colleagues Mr. Burns is an indispensable member of our group whose scholarly competence and accomplishments entitle him to recognition far beyond that yet accorded him by the University. At the earliest possible moment he should be advanced to an Associate Professorship.”

[…]

Source: Columbia University Libraries, Manuscript Collections. Department of Economics Collection, Box 3 “Budget, 1915-1946/1947”, Folder “Economics Budget, 1938-1939”.

____________________________

Department then begins unsuccessfully to push for an increase in salary with a promotion to Full Professorship

[Nov. 28, 1938]

[…] I respectfully recommend budgetary changes for the coming academic year 1939-1940, involving increase of compensation to the following members of the staff:

[…]

3. Arthur R. Burns from $4,000 to $4,500;

[…]

[Assistant] Professor Arthur R. Burns has established himself as an authority in his chosen field, and it is the desire of his colleagues that he be advanced to a full professorship as rapidly as university resources will allow. His tenure has already been long, and his advancement slow. It is our thought that he be given current recognition and enccouragement, with hope of promotion to rank commesurate with his repute among economists.”

[…]

Source: Columbia University Libraries, Manuscript Collections. Department of Economics Collection, Box 3 “Budget, 1915-1946/1947”, Folder “Economics Budget, “Economics Budget 1938-1939”. [note: incorrectly filed!]

____________________________

Requesting unpaid leave for a Twentieth Century Fund project

March 1, 1939

Nicholas Murray Butler, LL.D.

President of Columbia UniversityDear President Butler:

Professor Arthur R. Burns has been invited to take the directorship of a study of the public utility industry, under the auspices of the Twentieth Century Fund. We of the Department think it wise that he do this and recommend that he be granted leave of absence without pay for the academic year 1939-40. I shall be prepared before long to make recommendation of some outstanding person to serve as a partial substitute for Professor Burns during the coming academic year with a stipend which will absorb approximately three-fifths of Professor Burns’ current compensation.

Very sincerely yours,

Executive Officer

Department of Economics

Source: Columbia University Libraries, Manuscript Collections. Department of Economics Collection, Box 3 “Budget, 1915-1946/1947”, Folder “Economics Budget, 1939-1940”.

____________________________

Department repeats its recommendation for an increase in salary with a promotion to Full Professorship

[Nov. 18, 1939]

[…] I respectfully make the following recommendations affecting the budget of 1940-41:

[…]

6. That Assistant Professor Arthur R. Burns be granted added compensation of $500 [i.e. from $4,000 to $4,500].

[…]

[Assistant] Professor Arthur R. Burns has served a long apprenticeship with subordinate rank in the Department. At the moment, either from the standpoint of scholarly attainment or from that of efficiency in graduate instruction he suffers not at all by comparison with the best endowed and most effective of his colleagues. Because of his merits and of the importance of the field he covers, he should be advanced rapidly to full professorial status.

[…]

Source: Columbia University Libraries, Manuscript Collections. Department of Economics Collection, Box 3 “Budget, 1915-1946/1947”, Folder “Economics Budget, 1939-1940” [note: incorrectly filed!]

____________________________

Department repeats its recommendation for an increase in salary reducing promotion to Associate Professorship

[October 27, 1941]

MEMORANDUM

Department of Economics

October 27, 1941

[…]

Arthur R. Burns. Proposed: Advancement–assistant professor to associate professor.

Present salary $4,500

Proposed salary. $5,000[…]

Source: Columbia University Libraries, Manuscript Collections. Department of Economics Collection, Box 3 “Budget, 1915-1946/1947”, Folder “Budget Material from July 1941-June 1942”.

____________________________

Arthur R. Burns demands promotion to the rank of professor

3206, Que Street, N.W.,

Washington, D.C.

November 1st 1941.

Dear Professor Haig,

As I shall not be in New York this year to talk about the departmental plans for next year I must write. It seems to me that the question of my status in the department now calls for definitive action. Doubtless the unsettled times will be advanced as a reason for postponing promotion. At the outset, therefore, I wish to emphasise that I should regard any such attitude as entirely unfair. If the University is to go through hard times (as well it may) its misfortunes should be shared equitably among all the members of the faculty. To be frank, I feel that I have already been asked to bear an altogether unreasonable share of such financial stringencies as the University may have suffered. There have been many occasions in the past thirteen years on which I have been told that my promotion has been recommended (and more in which I have been told that it would have been recommended) but that no action has been taken for general financial reasons. I fully expect to bear my share of the burden of contemporary events but I feel that the time has come for my position to be given special consideration irrespective of those events, no matter how serious.

Various reasons have been given to me during my thirteen years of service to the University for its failure to promote me. But I think I am justified in believing that there has been less than the usual amount of criticism of my scholarship or my teaching capacity. The number of my students who have progressed in the outside world (sometimes already beyond my own rank and salary) indicates that I have been reasonably effective. Furthermore, I think that you will find that in recent years there has been an increasing number of graduate students coming to Columbia to work with me.

I now ask you, therefore, to have my academic status reviewed, whether or not the University wishes on principle again to avoid promotions. And after this long delay promotion only to an associate professorship will not, in my opinion, be compatible with my professional reputation and status. For six or seven years now my recognition outside the University has been widely at variance with my academic rank. My salary as Director of Research for the Twentieth Century Fund was $10,000 per annum. I have recently been invited to join the Anti Trust Division of the Department of Justice at a salary of $8,000 per annum. I am now the Supervisor of Civilian Allocation in the Office of Production Management. I suggest that this evidence justifies promotion to a full professorship. If economies are necessary, I am ready, as I have said, to accept them on the same basis as my colleagues.

I have written to you with complete frankness because I have been keenly disappointed with the disposal of suggestions for my promotion and I am anxious that you shall be clearly informed as to my feelings. I gather that for a number of years now there has been no serious objection but also no vigorous effort in my behalf. I now feel that if after all these long delays Columbia is unwilling to take special action to recognize my professional status I had better know before I am much older. I am now forty six years of age and if I must seek academic recognition elsewhere I must obviously begin to take the necessary steps without delay. I would of course prefer to stay with Columbia. I think you will agree that these long years of patient waiting are evidence of my loyalty but I think you will also agree that I cannot continue much longer to accept the present wide discrepancy between my status inside and outside the University.

Very sincerely yours,

[signed]

Arthur R. Burns

Professor Robert Murray Haig,

Chairman,

Department of Economics,

Fayerweather Hall,

Columbia University,

NEW YORK CITY

Source: Columbia University Libraries, Manuscript Collections. Department of Economics Collection. Box 2: “Faculty”, Folder: “Faculty Appointments”.

____________________________

Department responds to Burns’ demands:

Associate professorship when your rejoin the faculty

November 22, 1941

Professor Arthur R. Burns

3206 Que Street, N.W.,

Washington, D.C.

Dear Professor Burns:

Last night our group met at dinner to consider the budget. This afforded an opportunity to comply with your request that your academic status be reviewed. I wish you could have listened to the discussion that took place. It was highly friendly and appreciative in tone, but at the same time it was pervaded by a deep sense of responsibility for the ultimate objectives for which we are striving. I am sure that it would have impressed you, as it did me, with the essential soundness of the policy of placing heavy dependence upon the deliberate, critical judgment of one’s colleagues in considering questions of promotion.

Your letter of November 1st, which I read to the brethren in full, arrived at a time peculiarly unfavorable for the consideration of finalities and ultimatums. Moreover, I regret to have to report some of the statements and implications of that letter were not altogether fortunate in the reactions they inspired. Let me elaborate on this last statement first.

(1) You state that you gather that in the past there has been “no vigorous effort” in your behalf. I can speak with full knowledge only regarding last year. If the implication is that your failure to secure more adequate recognition is ascribable to lack of vigor on the part of your colleagues as a group, or of the chairman of the Department in particular, I wish to state that I know it to be untrue with respect to last year and have reason to believe it to be untrue of several previous years. As a matter of fact, last year as the program moved forward from the Faculty Committee on Instruction, the recommendation for your promotion was placed at the very top above all others in the Faculty of Political Science. Until the very end, when the Trustees at their March meeting ruthlessly scuttled the program, I had high hopes that the effort would be successful. The only budgetary changes last year in this entire Department of 32 members were a) a $300 increase for which the College authorities had obligated themselves to secure for Barger and b) the temporary allocation of $600 to Wald for one year only from a sabbatical “windfall”.

(2) The citation of the salaries and fees you have been able to command in the government service and in the service of private research organizations as evidence that “justifies promotion to a full professorship” does not greatly impress your colleagues. We rejoice in the recognition and rewards that have come to you in return for your efforts while on leave of absence from your post at Columbia. Certainly the work of the Department has been carried on under a distinct handicap when your courses haven manned by part-time substitutes and we should like to believe that the sacrifices involved had borne rich fruits in professional and material rewards to you personally as well as to the general cause of science. However, you will readily agree, I take it, that our promotion and salary policy cannot be based on the principle you seem to suggest, viz., that the University must be prepared to match, dollar for dollar, the potential earning power of the staff on outside jobs. The rate of compensation for such outside work is, to my certain knowledge, likely to run over four or five times the rate of University compensation. Indeed, I can think of many of our colleagues who, on the basis of such a principle, could cite evidence even more convincing than your own.

(3) In the next place your letter seems to imply an understanding of the nature of the University connection that is not in complete harmony with our own. While it may be the policy elsewhere that mere length of service by a person who joins the staff at an early age, even though that service be reasonably effective and untouched by unfavorable criticism, carries assurance of promotion to the highest rank, this is definitely not the policy at Columbia University. Theoretically, at least, the University retains complete freedom of action to withhold advancement subject to a continuing critical appraisal of the individual’s value to the institution, against the background of changing circumstances, among which the University’s ability to supply funds must be listed near the top. Everyone is continually on trial to the very end of his career. This is evidenced in the practice regarding early retirement, the working of which I have recently had an opportunity to observe. Assurance regarding stability of tenure at a given level is a different point and mere humanitarian considerations are given generous weight. However, fundamentally the University connection is to be regarded as an opportunity (an opportunity, incidentally, of which you, in the opinion of your colleagues have, on the whole, made very good use) and promotion and early retirement are certainly affected and, in many cases at least, determined by the manner in which a member of the staff rises to that opportunity. Moreover, when such heavy dependence is placed upon the continuing critical appraisal by one’s colleagues, each man must have regard for his responsibility for the long-run interests of the department and of science. If, as the years roll along, the department is to contain a reasonably large percentage of intellects of the highest order, the critical appraisal must be a continuing process and sufficient freedom of action must be retained in promotion and salary policy to enable the group to make reasonably effective its collective judgment as to what is best for the department in the light of the individual’s developing record and the fluctuations of the resources available for supplying opportunities. I hope that you will forgive me for laboring this point but it is important that you understand what I am certain is the sentiment of the group of which you are a valued member, viz., that no matter on what basis of rank you may return to us, say, for example, as an associate professor, further recognition in rank or salary will be dependent upon decisions reached in harmony with the general policies outlined above.

I now revert to my earlier statement that your letter arrived at a peculiarly unfavorable time.

(1) On November 13th a letter was received from the President of the University indicating that Draconian economies were indicated for this year’s budget. Our own enrolment in the graduate department of economics has shrunk this year about 25 per cent and this shrinkage is on top of last year’s substantial shrinkage. Even in advance of the preparation of the formal budget letters, the department chairmen were summoned before a special committee at the behest of the trustees and urged by the elimination of courses and other means to contract the normal budget to smaller proportions. Consequently only in emergency cases where the interests of the University are considered to be vitally affected, will serious consideration be given to recommendations involving an increased expenditure.

(2) With the retirement of McCrea, the question of the future of the School of Business has been thrown open for discussion. Under the new Dean a radical revision of policy is being formulated, including as one item the transfer of the School to a strictly graduate level. The intimate interrelationships of staff and curriculum between our department and the school are being reexamined. Plans are still in a state of flux but your particular field of interest is involved. So highly dynamic is the situation that the budget letters of both the Department and the School are to be considered tentative documents, subject to modification as decisions of policy are taken during the weeks that lie ahead.

(3) The situation is further complicated by the fact that within our Department itself we have reached the stage, which arises every decade or so, when long-time plans require consideration. Not only are we faced with an important retirement problem, but we are also asked to have regard for the situation that will result if the present trend toward lower enrolments continues. To deal with this situation, a special committee has been set up in the department, headed by Professor Mitchell, to formulate plans for the future. A series of meetings is being held at which the present and probable future importance of the various subjects falling within the scope of the departments are being discussed and questions of staff and curriculum are being intensively studied. Here also important decisions are in the making but definite conclusions have not yet been reached.

I am writing at such length in order that you may understand clearly and fully the background against which we were called upon to consider your letter and the reasons underlying the action that was taken in your case.

The recommendation that I am instructed by our colleagues to include in the budget letter is that I renew the recommendation made last year that you be promoted to the rank of associate professor at a salary of $5,000. I realize that this will be a disappointment to you. You have stated that you consider this degree of recognition, if we are successful in securing it for you, would not be compatible with your professional reputation and status. I infer from your letter that you consider it so inadequate that you are not prepared to accept it. However, you do not make yourself unequivocally clear on this point. If your mind is definitely made up, it will simplify the procedure if you will inform me of the fact at once. On the other hand, there is no disposition to press you for an early answer in case you are not as far along toward a decision as your letter would seem to imply.

In considering the problem of your probable future with us, as compared with the various flattering alternatives open to you, I feel that I should make the following statements:

(1) I have no assurance that the recommendation will be adopted. It will carry the vigorous support of the department and of the Chairman. I have already raised the question informally before the Committee on Instruction of the Faculty and am happy to be able to report that this committee is warmly friendly to your cause. Frankly, however, I am not as optimistic as I was last year at this time regarding the outlook for a favorable outcome when the trustees finally take action.

(2) I should report that, in view of all the circumstances, including the state of ferment that exists at the moment regarding future plans for the department, your colleagues would not be willing to urge your appointment to a full professorship immediately, even if they were convinced that such a recommendation would stand a chance of acceptance by the trustees. You are highly regarded and much appreciated. Your colleagues regret the harsh circumstances that have made it impossible to give you more recognition than you have already received. They consider you an excellent gamble for the long future. They consider the fields of your special interest important. However, it is hoped and believed that you have not yet reached a full development of your potentialities. When faced with the question as to whether they are convinced that, on the record to date, you are reasonably certain to be generally regarded, during the next twenty years, as one of the dozen or so most distinguished economists in active service, there is a general disposition to reply “not yet proven beyond a reasonable doubt”. Although they have no illusions about the difficulty of carrying out this policy with success, they have decided to take the position that they will henceforth recommend for a full professorship no one who does not meet such a test. They prefer to have you return with the clear understanding all around that the final issue, the question of the full professorship, shall not be decided in your case until more evidence is in. They take this position with the best of will and with a considerable degree of confidence that the final decision will be favorable. In connection with this, they feel that the important work upon which you are now engaged should contribute substantially to your “capital account” and should have a highly favorable effect upon your future record as a scholar and teacher.

You paid me the compliment of writing me a candid and forthright letter. In return I have attempted to lay before you with complete frankness all the considerations I know of that bear upon the question you have to consider.

Finally, I should like to say, speaking both in a personal capacity and as the chairman of the department, that I hope you will find it possible to send me word that you desire to continue as a member of our group under these conditions. We have an interesting and important task before us. I believe that you have a rôle to play in its accomplishment. If, unhappily for us, your decision takes you away from us, we shall sincerely regret the termination of our close association with you. To a remarkable degree you have earned for yourself not only the respect but the affection of your colleagues at Columbia.

Faithfully yours,

R.M. HAIG

P.S. At your early convenience will you be good enough to send me a note of any items that should be added to your academic record for use in my budget letter.

Source: Columbia University Libraries, Manuscript Collections. Department of Economics Collection. Box 2: “Faculty”, Folder: “Faculty Appointments”.

____________________________

From: Economics Department’s Proposed Budget for 1946-1947

November 30, 1945

[Burns recommended for professorship]

[…]

We recommend that Arthur Robert Burns, now an associate professor at a salary of $5,000, be promoted to a professorship at $7,500. Professor Burns, who has been connected with the University since 1928, was appointed an assistant professor in 1935, an associate professor in 1944. He has returned this year to his academic work, after a six-year leave of absence devoted to research and to important governmental service. His war-time activities have included service as Chief Economic Adviser and deputy Director of the Office of Civilian Supply, Deputy Administrator of the Foreign Economic Administration, and a mission to Europe in 1945 as a member of the American Group of the Allied Control Commission, advising on economic and industrial disarmament of Germany.

Professor Burns is carrying one of the fundamental graduate courses on Industrial Organization. He has agreed to offer one of the courses that will be central in the curriculum of the School of International Affairs–a course on “Types of Economic Organization”. His close acquaintance with the organization of the economies of the United States, Britain, and Germany, and his scholarly background in the field are of great value in this development of systematic academic work on comparative economic systems. Burn’s scholarly reputation is high. His study of The Decline of Competition, which is accepted as a standard in the field, is one of the major products of the Columbia Council on Research in the Social Sciences. He has served the country in recent years in administrative and advisory posts of high responsibility. We believe that he should have the rank of full professor.[…]

Annex C

ARTHUR ROBERT BURNS

Academic Record

1918. Gladstone Memorial Prize, London School of Economics, London.

1920. B.Sc. (Economics) degree with First Class Honors, University of London.

1926. Ph.D. degree, University of London.

1926-28. Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial Fellowship.Teaching

1922-26. University of London.

1928-31. Lecturer in Economics, Barnard College, Columbia University.

1931-35. Lecturer in Economics, Faculty of Political Science, Columbia University.

1935-44. Assistant Professor of Economics, Faculty of Political Science, Columbia University.

1939. Special Lecturer, Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania.

Leaves of absence without salary for 1940-41 through 1944-45.

1944-45. Promoted to Associate Professor of Economics

Returned to Columbia University for 1945-46.Published Work

“Indian Currency Reform.” Economica, about 1925.

“The Effect of Funding the Floating Debt,” Economica, about 1933.

“Money and Monetary Policy in Early Times.” London: Kegan Paul & Co., 1927. About 650 pp.

“The Economic World.” London, University of London Press, 1928. [sic: co-authorship of wife Eveline M. Burns was not included in the citation].

“The Quantitative Study of Recent Economic Changes in the United States.” Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 31: 491-546, April, 1930.

“Population Pressure in Great Britain.” Eugenics, 3: 211-20, June, 1930.

“The First Phase of the National Industrial Recovery Act 1933”. Political Science Quarterly, 49:161, June, 1934.

“The Consumer under the National Industrial Recovery Act.” Management Review, 23:195, July 1934.

The Decline of Competition. New York, McGraw Hill, 1936. 619 pp.

[not listed: “The Process of Industrial Concentration” 47 Q.J.E. 277 (1933)]

“The Anti-Trust Laws and the Regulation of Price Competition.” Law and Contemporary Problems, June, 1937.

“The Organization of Industry and the Theory of Prices.” Journal of Political Economy, XLV: 662-80, October, 1937.

“Concentration of Production,” Harvard Business Review, Spring Issue, 1943.

“Surplus Government Property and Foreign Policy”, Foreign Affairs, April, 1945.Unpublished Studies

1935-38. Investigation of the pricing of cement with special reference to the basing point system (in collaboration with Professor J. M. Clark).

1939. Report on the pricing of sulphur.

1938-39. Study of distribution costs and retail prices.

1939-41. Director of Research, Twentieth Century Fund study of “Relations between Government and Electric Light and Power Industry.” Has been completed and is now in hands of the Twentieth Century Fund.Other Work

1935. Alternate member. President’s Committee to report on the experience of the National Recovery Administration.

1938-39. Chairman, Sub-Committee of Price Conference on Distribution Costs and REtail Prices.

1939-41. Member of Board of Editors, American Economic Review.

1941. Supervisor of Civilian Supply and Requirements, Office of Production Management.

1942. Chief Economic Adviser, Office of Civilian Supply, War Production Board.

1942 (July-August). Member of mission to London to study British methods of concentration of industry.

1943. Deputy Director, Office of Civilian Supply.

1943. Director of Planning and Research, Office of Civilian Requirement

1943, December to March, 1945. Special assistant to Administrator, Deputy Administrator to the Foreign Economic Administration.

1945-continuing. Consultant to Enemy Branch of the Foreign Economic Administration.

1945, Summer. In Europe with the American Group of the Allied Control Commission to advise on the economic and industrial disarmament of Germany.

Source: Columbia University Libraries, Manuscript Collections. Department of Economics Collection, Box 3 “Budget, 1915-1946/1947”, Folder “Department of Economics Budget ’46-47 and related matters”.

___________________________

Obituary: “Arthur Robert Burns dies at 85; economics teacher at Columbia“, New York Times, January 22, 1981.

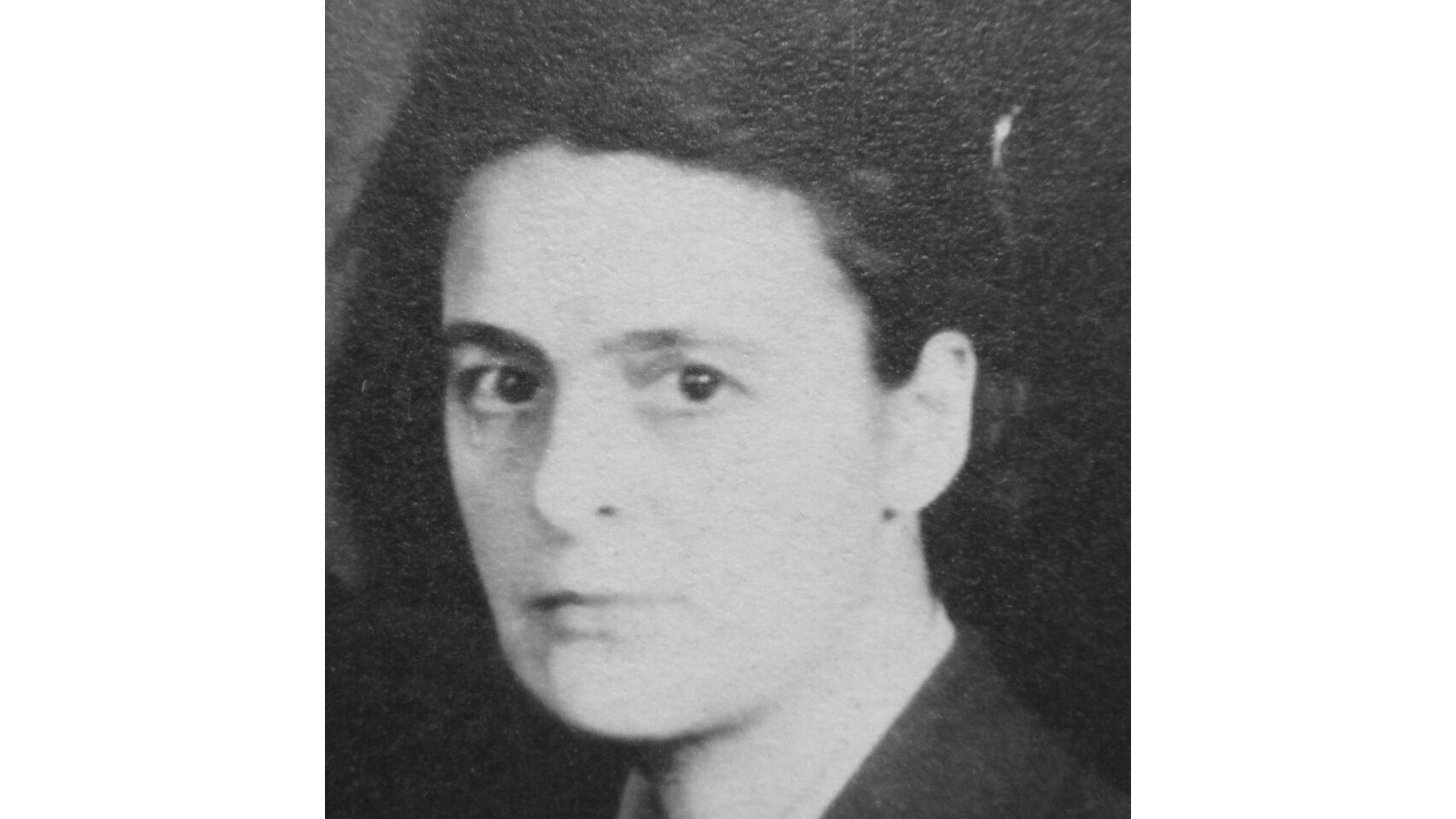

Image: Arthur Robert Burns. Detail from a departmental photo dated “early 1930’s” in Columbia University Libraries, Manuscript Collections, Columbiana. Department of Economics Collection, Box 9, Folder “Photos”.