The issue of academic freedom can shock the best and worst of economics departments. Like much of what is interesting in economics, it is important to distinguish between nominal and real shocks. In 1933 Columbia College, the undergraduate arm of Columbia University, found itself in a whirlwind of controversy following the non-renewal of a contract of a radical instructor of economics. I stumbled across this case from newspaper accounts and thought it would help spice up Economics in the Rear-view Mirror (much as the Harvard/UMass saga of young radical economists in the early 1970s has) to examine the case.

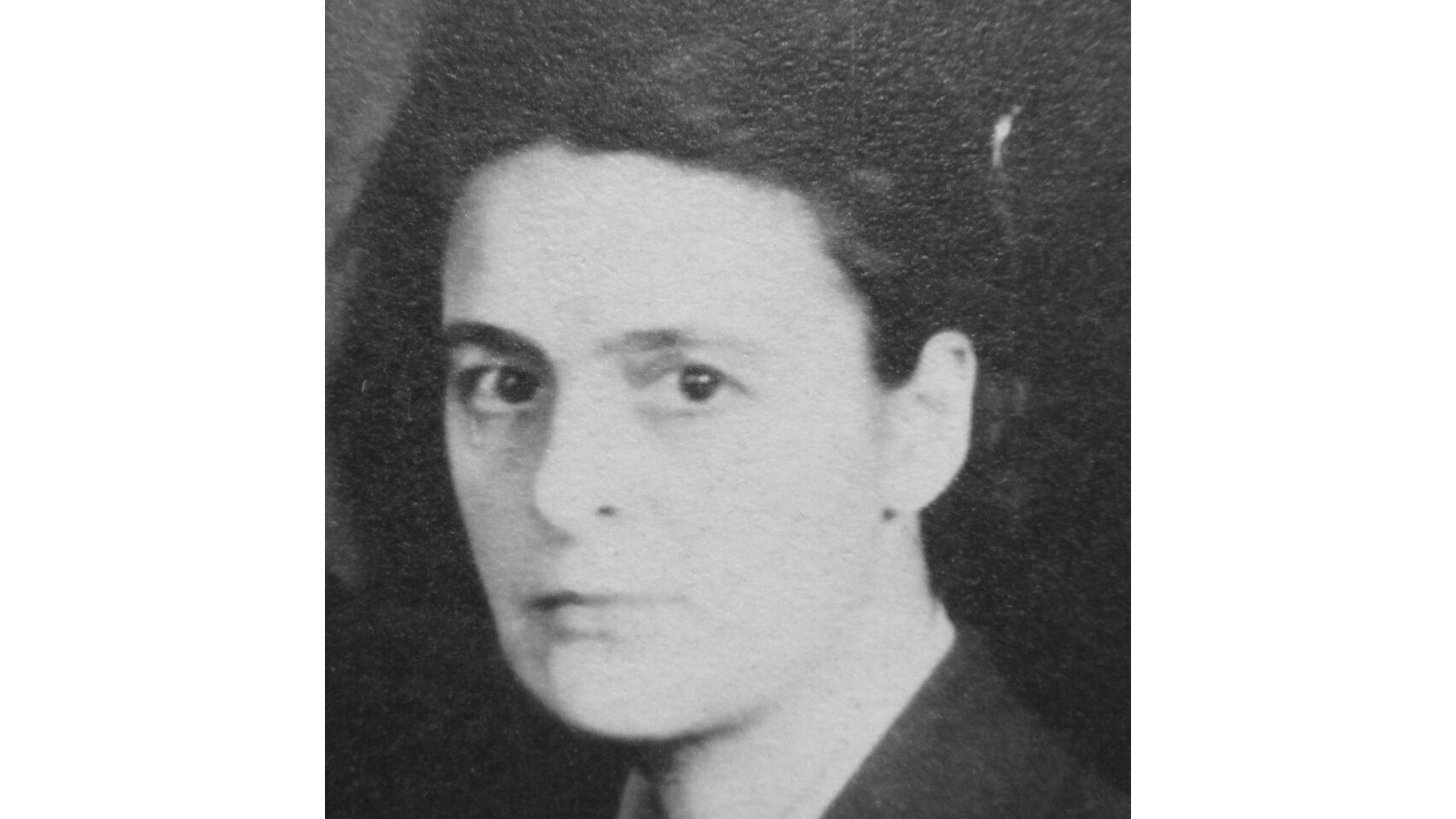

I have not ever looked for or seen any archival material at Columbia regarding the protagonist of this post, Donald Henderson. Economics in the Rear-View Mirror is primarily concerned with the nuts-and-bolts of the economics curricula across time and universities. Still my curiosity has led me to examine several online newspaper archives (The Columbia Spectator archive has been especially useful), the genealogical website ancestry.com, and the usual book/text sites (archive.org and hathitrust.org), to fill in missing details about the life of Mr. Donald Henderson.

Economics in the Rear-View Mirror, theory of the case: Columbia University’s upper administration appears to have had a “Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?” moment once alumni letters began to pour in following the arrest of its economics instructor, Donald Henderson, at a protest in October 1932 at C.C.N.Y. in support of the English instructor Oakley Johnson, who had been dismissed by City College President Frederick B. Robinson for his “communist sympathies” (a New York Times understatement). Having left the safe-space of what goes in Vegas, stays in Vegas (i.e. Columbia College), Donald Henderson was a low-value academic pawn offered as a sacrifice to satisfy the alumni gods. Henderson had not really displayed visible indicators of a future distinguished academic career and the Columbia administration most certainly underestimated the potential of the organized mobilization by militant agitators capable of leveraging such an issue for less than pure academic freedom principles. At the time the Columbia Spectator editorial board framed the problem essentially as one of academic freedom vs. academic license.

Who was Donald Henderson? In the historical record we find that Henderson went on to become a communist party labor organizer who had climbed high enough in U.S. union leadership circles to even attract a subpoena from no less an assistant United States Attorney than Roy M. Cohn (yes, that Roy M. Cohn, whose later client list would include… Donald J. Trump…small world?!). Some Congressional testimony with Henderson’s liberal invocation of the Fifth Amendment regarding his communist party activities is provided below. With this his labor organizing career ended in the early 1950s and he lived the rest of his life in obscurity in Miami, Florida.

Now some artifacts following a chronology of Donald Henderson’s life.

______________________

Donald James Henderson

Timeline

1902. Born February 4 in New York City to Jean Henderson née Crawford and Daniel Robert Henderson (occupation “coachman” according to the 1898 birth certificate for his older sister Marjorie Augusta Henderson).

1910. According to the 1910 U.S. census Mother Jean (“Married”) and all four children were living with their grandmother Estelle I. Crawford in Montpelier, Vermont where Donald went to grammar school. Donald’s father Daniel not yet found at this address or elsewhere).

1913. Donald’s father Daniel remarries August 18 to Hesper Ann Joslin.

1920. According to the 1920 U.S. census Mother Jean (“Divorced”) and all four children were still living with their grandmother Estelle I. Crawford in Dansville, New York where Donald went to high school.

1921-22. Likely start of Donald Henderson’s undergraduate studies at Columbia University.

1924. The Columbia Progressive Club reorganized November 13. Purpose of the club was the furtherance of a Third Party Movement. Members of the Executive Committee included Elinor Curtis and Donald Henderson.

1925. Donald J. Henderson married Elinor Curtis (Barnard, 1925) in Manhattan, August 31.

1925. A.B. with general honors, Columbia College.

1925-26. Garth Fellow, Columbia University.

1926. M.A. Columbia University.

1926. Birth of first son, Curtis Henderson (1926-2009) in New York City, September 28.

1926-27. Instructor in Economics, Rutgers University. Listed for a course on the economics (and regulation) of railroads, water, and motor transportation; a course on statistical principles.

1927-28. Summer Session [rank unclear], Columbia University.

1928-29. Instructor of Economics, Columbia University.

1929-30. Instructor in Economics. Columbia University.

1930-31. Instructor in Economics. Columbia University.

1931-32. Instructor in Economics. Columbia University.

1931. Communist Daily Worker of August 4, 1931. Henderson declared that he had rejected socialism and joined the Communist Party.

1932-33. Instructor in Economics. Columbia University.

1932. His wife, Elinor C. Henderson ran for Congress as an independent (i.e. as communists then did) in the 21st New York congressional district, receiving 7/10th of one percent of the vote.

1932. Arrested October 26 with three C.C.N.Y. students for disorderly conduct after police broke up a meeting protesting the dimissal of English instructor at C.C.N.Y., Dr. Oakley Johnson.

1932. Serving as executive secretary of the American Committee for Struggle Against War, the American branch of the World Congress Against War. Active in the Student Congress Against War and Fascism (established at Christmas).

1933. April. Donald Henderson’s appointment as instructor of economics is not renewed for the coming academic year. Joint committee [the Columbia Social Problems Club, Socialist Club, Barnard Social Problems Club, Economics Club, Mathematics Club, Sociology Club of Teachers College and the Social Problems Club of Seth Low] organizes campus protests for the reappointment of Henderson.

May. Further demonstrations, Henderson case attracts national attention.

“Diego Rivera Addressing Striking Students at Columbia,” New York Times, May 16, 1933, p. 3.

“Diego Rivera Addressing Striking Students at Columbia,” New York Times, May 16, 1933, p. 3.

Note: The painter Diego Riviera was Frida Kahlo’s husband.

1933. Executive secretary of the United States League Against War and Fascism that met in New York on September 29.

1933-34. Began organizing agricultural workers across the United States for the American Federation of Labor.

1934. Daily News (New York). From Bridgeton, N.J., July 10. Wire photo caption: “Husky Official leads Donald Henderson by the wrist as police spirit the Red organizer away from meeting where striking workers at Bridgeton, N.J., threatened him with lynching.”

1935. Second son, Lynn Henderson born in New York, April 14.

1935. September. Wrote article “The Rural Masses and the Work of Our Party” in The Communist.

[e.g. “… during the past 2 years our party has been successful in developing policies and organization which are rapidly achieving a successful turn to mass revolutionary work and influence in the cities and among the industrial urban proletariat.”]

1937. Established the United Cannery, Agricultural, Packing and Allied Workers of America, affiliated to the CIO. Elected as its international president, holding the post to 1949.

1938. [ca.] Third son, Donald Henderson, Jr. born.

1941. Wife, Eleanor [sic] Curtis Henderson died of poisoning June 11 in their home at 7750 South Sangamon Street, Chicago. “A coroner’s jury returned a verdict saying that it was unable to determine whether or not Mrs. Henderson took the poison accidentally.” Chicago Tribune (June 12, 1941, p. 12).

1943. Married South African born actress, Florence Mary McGee [formerly Thomas from her first marriage], in New York City, October 10.

1944. “United Cannery, Agricultural, Packing and Allied Workers of America” changes its name to the “Food, Tobacco and Agricultural Workers Union”.

1948. From The South Bend Tribune, Indiana (November 23, 1948), p. 1. “Donald Henderson, of Philadelphia, Pa., president of the Food & Tobacco Workers, was halted repeatedly by CIO convention delegates booing the minority report he read at Portland, Ore., opposing continued CIO support of the Marshall plan.”

1949. April. Henderson attends the (Soviet dominated) World Federation of Trade Union meeting in Paris as president of the Food, Tobacco and Agricultural Workers Union.

1949. Communist Daily Worker of August 15, 1949, entitled “FTA complies with NLRB rule”. Henderson quoted: “While it is true that I had been a member of the Communist Party, I have resigned my membership therein…” [For the union to be in compliance with the Taft-Hartley Act and have its officers sign the non-Communist affidavit, Henderson stepped down as president and was immediately appointed National Administrative Director.]

1950. October. Food, Tobacco and Agricultural Workers Union merged with the Distributive Workers Union and the United Office and Professional Workers Union to form a new international union called the Distributive, Processing and Office Workers Union of America (DPOWA). Served as administrative secretary of that international union for the first year.

1951. October. Reorganization of the DPOWA. Elected to national secretary-treasurer. [Henderson held post at least to Feb. 14, 1952 when he testified before U.S. Senate, Subcommittee to investigate the administration of the internal security Act and other Internal Security Laws of the Committee on the Judiciary.]

1951. Received a 30 day sentence for disobeying a Judge’s injunction against mass picketing during a brief strike at the Pasco Packing Company plant. “Donald Henderson of New York” head of the Food, Tobacco, Agricultural and Allied Workers Union (Ind.). From an Associated Press report, Dade City (Sept. 26) in Pensacola News Journal Sept. 27, 1951, p. 9.

1953. From a United Press report from Washington, February 23 published in The Palm Beach Post (February 24, 1953): “Henderson, now secretary-treasurer of the Distributive, Processing and Office Workers of America (ind)” took the fifth amendment before the Senate Permanent Investigating Committee of Sen. Joseph R. McCarthy. He also refused to answer questions about Voice of America employees with suspected communist affiliations.

Post-McCarthy hearing years. “[Henderson] eventually had to become a salesman to earn a living.” [From his obituary in The Militant, December 28, 1964]

1957. The Miami News (January 26, 1957, p. 18). Report that Florence McGee moved to Miami recently with her husband, Donald Henderson, and their son. They have “been living quietly at 4335 [or 4345] SW 109th Ct.) She apparently resumed her long-paused acting career in the drama “Teach Me How to Cry” at Studio M.

1958. “By 1958 the illness which eventually took his life forced him into complete inactivity.” [From his obituary in The Militant, December 28, 1964]

1964. Donald Henderson died of a kidney ailment in Miami, Florida in December 12. [From his obituary in The Militant, December 28, 1964]

2000. Florence McGee Henderson (97 years) died in Miami, Florida on June 16.

_________________________

Obituary

THE MILITANT

(New York, NY)

28 Dec 1964

Early Organizer of Tobacco Union Dies in Florida

Donald Henderson, 62, a prominent early organizer of agricultural and cannery workers, died of a kidney ailment in Miami Dec. 12.

Henderson was an economics instructor at Rutgers and Columbia University in the mid-1920s. During this period he played a key role in the student and anti-fascist movements and was active in organizing the National Student Union and the American League Against War and Fascism. These activities led to his dismissal from Columbia.

He then devoted his efforts to the organization of agricultural workers, at that time completely unorganized in the U.S. Beginning by organizing workers in the truck farms of New Jersey, he established the Food, Tobacco and Agricultural workers union. The FTA under his leadership became one of the largest agricultural unions in the US, with a large membership of Southern Negroes, Mexican-Americans in southern California.

The deepening of the cold war, resulted in the expulsion of a large number of “left-wing” unions, including the FTA, from the CIO in 1950.

Henderson was an unco-operative witness at the McCarthy hearings in the 1950s and eventually had to become a salesman to earn a living. By 1958 the illness which eventually took his life forced him into complete inactivity.

______________________

Articles in

Columbia Daily Spectator

Columbia Daily Spectator, Volume LVI, Number 22, 28 October 1932.

Henderson Released on Bail

For Disorderly Conduct Hearing

Columbia Instructor, Held After Meeting

at C.C.N.Y. to Face Trial

Donald Henderson, Instructor in the Department of Economics, who was arrested on Wednesday night on a charge of disorderly conduct in connection with a demonstration at City College, was released on bail yesterday after arraignment in Washington Heights Court.

Mr. Henderson and three C.C.N.Y. students, who were held following a meeting of the Liberal Club at City College to protest the dismissal of Oakley defendants. Magistrate Anthony F. Burke ordered bail of $500 for each of the four under arrest. Their release could not be secured until later in the afternoon.

The seizure of Mr. Henderson came after the Liberal Club had been ejected from its meeting room in the College and had taken its stand on the Campus. There, after several denunciatory speeches, he was apprehended by the police and taken to night court where Magistrate Dreyer postponed the hearing until yesterday.

It is understood that the Columbia Social Problems Club will take steps to protest Mr. Henderson’s detention at a meeting of that organization at noon today in Room 307 Philosophy.

Frank D. Fackenthal, Secretary of the University, when asked whether the University would make any official recognition of the case, said that., the “matter is out of my jurisdiction.”

About 100 students from Columbia and C.C.N.Y. jammed the courtroom to hear the trial, with an equal number milling about outside and listening to speeches condemning the police action…

* * * * * * * * * * *

Columbia Daily Spectator, Volume LVI, Number 25, 2 November 1932.

Trial Begins For Henderson

Hearing Opens Before Crowded Courtroom.

Resumes Session Today

With the courtroom jammed to capacity and 200 students milling about in the streets outside listening to denunciations of the C.C.N.Y. administration, the trial of Donald Henderson, instructor in Economics at Columbia, arraigned on a charge of disorderly conduct, opened yesterday in Washington Heights Court before Magistrate Guy Van Amringe.

Mr. Henderson held with three City College students following a demonstration protesting the dismissal of Oakley Johnson from the C.C.N.Y. faculty, will reappear at 2:30 this afternoon for further hearing.

Session Lasted Three Hours

Yesterday’s session lasted for nearly three hours, with the proceedings devoted largely to the calling of witnesses for both sides. Mr. Henderson is expected to take the stand today, with Allan Taub acting as counsel for the defense.

Dr. George Nelson, assistant librarian at City College, testified yesterday that on the night of the disturbance which resulted in the arrests, he entered the history room of the College and found fifty students meeting there. They refused to leave, he said, and he summoned several policemen.

State Henderson Refused to Leave

Henderson: remained adamant, Nelson charged, and was finally pushed out of the room. Nelson added that he did not see the other defendants.

Oakley Johnson, whose removal led to the series of demonstrations in which Columbia students took a prominent part, appeared at the trial and was at first denied admittance. He finally gained entrance after several disputes.

* * * * * * * * * * *

Columbia Daily Spectator, Volume LVI, Number 29, 9 November 1932.

Henderson on Probation

After Conviction For Disorderly Conduct

Donald Henderson, instructor in Economics, who was tried on a charge of disorderly conduct as a result of his participation in a demonstration protesting the dismissal of Oakley Johnson from C.C.N.Y., is on probation for six months after receiving a suspended thirty day sentence.

The trial, conducted before Magistrate Guy Van Amringe in Washington Heights Court, was brought to a close Monday after a week of prolonged hearings. Allen Taub acted as counsel for the defense….

* * * * * * * * * * *

Columbia Daily Spectator, Volume LVI, Number 112, 5 April 1933.

Henderson Appointment Ended;

Conflicting Explanations Issued

Donald J. Henderson, instructor in economics and prominent radical leader, clashed with the University yesterday over the non-renewal of his appointment here, in the first phase of what loomed last night as a prolonged conflict between Mr. Henderson’s supporters and the Administration.

Mr. Henderson, in declaring that he had rejected a Fellowship tendered to him by the University following the termination of his teaching activities, said that the offer was “a maneuver to ease me out of the University without raising the issue of academic freedom.”

Concerning that allegation, Professor Roswell C. McCrea, head of the Department of Economics, maintained that Mr. Henderson, during his tenure at Columbia, “has engaged freely in any activities to which he may have been attracted.

“The fact that his position here,” Professor McCrea insisted, “was not a permanent one was clearly stated to him before he became actively connected with any political group.”

With Mr. Henderson’s stand apparently clearly defined by his statement, the Social Problems Club, with which he has been actively connected, revealed yesterday that it will meet at 3:30 this afternoon in Room 309 Business to develop “a line of action” to be followed in Mr. Henderson’s defense.

Immediately following the appearance of the College Catalogue on Monday, in which no mention is made of Mr. Henderson, widespread curiosity was current as to his future status. That question was clarified with the issuance of statements yesterday by Mr. Henderson and Professor McCrea.

The statements, sharply conflicting on several points, dealt with the circumstances of Mr. Henderson’s seemingly imminent departure from Morningside Heights.

Mr. Henderson, who has been a prominent figure in radical disputes on this Campus and elsewhere, charged that the University is “maneuvering to ease me out without raising any question of academic freedom,” whereas, he declared, “the facts in this situation raise clearly and definitely the issue of academic freedom.”

In regard to his radical exploits which have been the subject of frequent newspaper comment, Mr. Henderson said that he was told last Spring that “extreme pressure was being brought to bear for my removal.”

Says Protesting Letters Received

He maintained that Professor Rex C. Tugwell informed him the following summer that “a flood of letters from prominent Alumni” had been received protesting the activities of Mr. Henderson and his wife, who was jailed during a dispute over alleged discrimination against Negroes.

Declaring that Mr. Henderson has “failed consistently to apply himself seriously and diligently to his duties as instructor and to maintain the standards of teaching required by this Department,” Dean McCrea said that “those conditions make his further connection with the Department of Economics undesirable.”

Mr. Henderson made known that he had been offered a post as “Research Assistant” for one year by the University “at a salary $700 less than my present one.”

Cites Provision of Offer

“The one condition attached to this offer,” he claimed, “was that the year be spent in the Soviet Union… the subject matter of my thesis, with which Professor Tugwell is acquainted, requires research in the United States rather than the Soviet Union.”

Professor McCrea’s statement declared that non-renewal of Mr. Henderson’s contract “is consistent with long-established University policy.

“There never has been any understanding or intention that Mr. Henderson should stay permanently at Columbia…. An appointment to an instructorship does not imply, in any case, later appointment to a higher rank with more permanence of tenure. For this reason, such understandings are had with all graduate students who are appointed to instructorships in economics.”

Mr. Henderson said that in the summer of 1931 “I became more active in the revolutionary movement and received considerable publicity in the newspapers in connection with those activities.

“That fall,” he continued, “I was advised by Professor Tugwell to look for another job. He stated at that time that in case of lack of success in finding another position, I would not be dismissed.”

* * * * * * * * * * *

Columbia Daily Spectator, Volume LVI, Number 112, 5 April 1933.

Somebody’s Wrong

[Spectator editorial]

The statement issued yesterday by Mr. Donald Henderson obviously does not quite jibe with that of Professor Roswell McCrea. According to one statement, Mr. Henderson was not reengaged as an instructor because of his radical activities, while according to the other the close of his academic career in so far as Columbia is concerned was occasioned by his incompetence as a scholar and as a teacher. There is no denying that Donald Henderson was the most obstreperous of Columbia’s many radicals. As to his teaching ability only those who have been his pupils can testify. Radical activities are certainly not a just cause for dismissal from the faculty of a liberal university. But it is equally as certain that it is unjust to use an instructor’s radical activity as an implement with which to force a university to handle with kid gloves a disinterested and incompetent instructor.

* * * * * * * * * * *

Columbia Daily Spectator, Volume LVI, Number 113, 6 April 1933.

Problems Club Begins Defense of Henderson.

Committee Formed to Outline Campaign for Reappointment of Radical Instructor

– Attacks Dismissal

Mobilization of Donald Henderson’s defense in his clash with the University over non-renewal of his appointment was begun by the Social Problems Club yesterday.

While Mr. Henderson, an instructor in the department of economics and widely known radical leader, issued a second statement in which he characterized Professor Roswell McCrea’s assertions as “false” and “absurd,” the Club appealed for “effective and widespread action” in his support.

Committee of Ten Chosen

The latter move followed a meeting of the Club yesterday afternoon when a committee of ten was elected to direct the campaign for Mr. Henderson’s reappointment. The committee held its first session immediately after the club meeting and announced that it would convene again this afternoon to formulate “a complete program of action.”

At the same time Dr. Addison T. Cutler, instructor in economics and a member of the committee, made public four letters he said came from students who have studied under Mr. Henderson. These letters, “from students not affiliated with the Social Problems Club,” were introduced in defense of Mr. Henderson’s teaching ability.

Declares Action Due to ‘Pressure’

In his statement which was prompted by the declaration of Professor McCrea on Tuesday concerning Mr. Henderson’s status, the latter amplified his previous testimony in which he claimed that the University’s action was the result of “extreme pressure” growing out of his political activities.

“The assertion by Professor McCrea Mr. Henderson said yesterday, that I was engaged to teach in Columbia University on the condition that I finish my work for the doctor’s degree in two years is absolutely false.

Calls McCrea’s Statement ‘Absurd’

“As in the case of all instructors who are engaged at Columbia without doctor’s degrees, it was understood that I should continue my graduate work as rapidly as possible. The records will show that I have done this; all course credits and course requirements have been disposed of.”

Stating that he has been engaged in research on his thesis—”The History of the American Communist Party”—for the past two years, Mr. Henderson further charged that “the entire question of scholarly competence raised by Professor McCrea is absurd in view of the offering to me of a research assistanceship by the same department.

“The latter certainly could not be based on a disbelief in my scholarly competence.” The Problems Club will seek to enlist the support of other Columbia organizations, it was said yesterday.

The club’s statement asserted that “the Social Problems Club has been aware of administrative opposition to Mr. Henderson for many months. A careful effort has been made by the administration to get rid of Mr. Henderson without raising the issue of academic freedom.”

Charging that Mr. Henderson was “dismissed because of his political activities,” the statement called upon Spectator “to give the same dignified but vigorous support of academic freedom in Henderson’s case as did Henderson in the case of Spectatorat this time last year.”

In that regard, it was recalled yesterday that the strike on this Campus last year protesting the dismissal of Reed Harris took place exactly one year ago today.

* * * * * * * * * * *

Columbia Daily Spectator, Volume LVI, Number 115, 10 April 1933

Joint Committee Outlines Action On Henderson

Issues Statement on Case Preliminary to Drive for Widespread Support

25,000 Leaflets To Be Distributed

In the first major move of what portends to be a nationwide campaign for the reappointment of Donald Henderson, the Columbia Joint Committee representing the Social Problems and Socialist Clubs yesterday issued a statement laying the groundwork for its program of action in Mr. Henderson’s defense.

The declaration was formulated in concert by the two organizations which are assuming the initiative in the movement for reappointment of the prominent Campus radical leader to his present post in the Economics Department.

To Seek Nationwide Aid

It deals with the case as presented by Mr. Henderson last week and as set forth by Professor Roswell C. McCrea in explanation of the Administration’s stand. Twenty-five thousand copies of the statement are being printed for distribution among organizations throughout the country in an effort to enlist “widespread and effective” support, it was announced last night.

The statement takes up successively the question of Mr. Henderson’s status under three main divisions —”The University’s Excuses,” “The Great Maneuvre That Failed” and “Pressure for Henderson’s Removal.” It concludes with a plea for “all students, student groups and faculty members to send letters of protest to Professor Roswell C. McCrea in Fayerweather Hall.”

Lays Dismissal to Radicalism

“No one knows better,” the declaration asserts, “than the Columbia administration that Mr. Henderson has been dropped because of his political activities and his leadership in the student movement of America.”

The committee outlines “The University’s Excuses” as based on three grounds—the non-permanence of Mr. Henderson’s appointment, non-completion of his degree and his teaching ability.

Questions Second Charge

On the first point, the statement says that “no one claims the University is violating a legal contract in dropping Henderson.” It takes issue, however, with Professor McCrea’s assertion that Mr. Henderson’s original appointment was made “on the condition that he finish his doctor’s degree within two years.” Concerning Mr. Henderson’s failure to achieve his Ph.D., the statement asserts that “neither have many other instructors who have been teaching for many years at Columbia” and states he “has finished all course and credit requirements.” Professor McCrea’s reference to Mr. Henderson’s teaching ability is branded “the most contemptible charge of all, unsupported by facts.”

Professor McCrea had said “Henderson has failed consistently to apply himself seriously and diligently to his duties as instructor and to maintain the standards of teaching required by the department.”

Cites Praise of Henderson

The Joint Committee here offers commendatory avowals “by former students who are neither personal friends of Henderson or associated with his political activities, including honor students, football players and others.”

The statement takes note of the action of Mr. Henderson’s Economics Seminar which unanimously voted him “a competent instructor” and “his analysis of economic theory… illuminating and intellectually stimulating.”

Statement Attacks Fellowship Move

Turning to “The Great Maneuvre That Failed,” the Committee considers the offer of a fellowship to Mr. Henderson by the University, which he declined, he said, as a move “to ease me out of the University without raising any question of academic freedom.”

In the section devoted to “Pressure for Henderson’s Removal,” the committee declares that at the time of the student strike last year in which Mr. Henderson played an active part, “Professor Tugwell said that it was only a question of time how long the pressure (for Mr. Henderson’s removal) could be withstood.

* * * * * * * * * * *

Columbia Daily Spectator, Volume LVI, Number 117, 12 April 1933

To the Editor of Spectator:

The following is a statement of facts concerning a conversation I had with Dean Herbert E. Hawkes; I pass it on to you in the hope that it may shed light on the refusal of the administration to renew the appointment of Donald Henderson:—

The conversation took place in the Dean’s office in January, 1932. Only the Dean and I were present. We were engaged in a discussion of the teaching staff of Columbia College.

It was Dean Hawkes’ contention that the quality of instruction afforded students in the College was fully as distinguished as that to be had in any other university in this country.

To illustrate this argument he placed before me a list of the professors and instructors in the College. He read the names of the instructors, amplifying his reading with short summaries of the merits of the men in question.

I remember very clearly that he had high praise for every name on the list except of Mr. Henderson. The Dean said: “Mr.” Henderson is the only weak man we have. We are not satisfied with his work. I don’t think he will be with us next year.”DONALD D. ROSS ’33 A.M.

* * * * * * * * * * *

Columbia Daily Spectator, Volume LVI, Number 117, 12 April 1933

Group Will Hold Protest Meeting On Henderson

Joint Committee Fixes Next Thursday as Date

Site Not Yet Chosen

Will Picket Library on Wednesday

The campaign for the reappointment of Donald Henderson, instructor in economics, yesterday focused on the efforts of the Columbia Joint Committee, organized to carry on his defense on this Campus.

Following a meeting attended by representatives of Columbia organizations, two principal decisions emerged:

- An outdoor demonstration will be held on Thursday, April 20, at a principal point, still undetermined, on the Campus.

- Pickets will be designated to surround the Main Library a week from today in preparation for an open-air meeting the following day.

Seven Clubs Send Members

While non-Campus groups were coming to the aid of the Columbia Committee, seven clubs from the University sent delegates to the meeting which determined upon the outdoor demonstration and the picketing plan.

These groups include:

The Columbia Social Problems Club, the Socialist Club, the Barnard Social Problems Club, the Economics Club, the Mathematics Club, the Sociology Club of Teachers College and the Social Problems Club of Seth Low.

Leaflets Distributed on Campus

2,000 leaflets bearing the title, “The Henderson Case” and containing the statement issued last Sunday by the Joint Committee were distributed on the Campus yesterday with 3,000 additional copies to be delivered today.

Meanwhile, the plan to enlist support from organizations throughout the country continued apace with the National Student League circularizing groups on 100 campuses. A city-wide meeting on the case will be held this Saturday at the New School for Social Research when delegates will be sent from the National Student League, the Intercollegiate Council of the League for Industrial Democracy, the Student Federation of America and other groups.

Teachers Send Protest

The Association of University Teachers yesterday sent a telegram of protest to President Nicholas Murray Butler and Professor Roswell C. McCrea. It read: “The Association of University Teachers, having examined all evidence available believes the dismissal of Donald Henderson unjustified and urges his reappointment.”

It was also made known that the Association has appointed a committee to cooperate in the campaign for Mr. Henderson’s reappointment.

The pickets will be stationed at positions around the Main Library where the offices of several prominent administrative officers are situated.

The Joint Committee yesterday made public a letter from Professor McCrea addressed to Miss Margaret Schlauch, a graduate of the University. Miss Schlauch has written protesting the nonrenewal of Mr. Henderson’s contract.

McCrea Replies to Letter

Professor McCrea, in reply, stated that “unfortunately, I fear that the public fails to understand the real merits of the situation. “These I think were adequately set forth in a statement which was furnished to the press but which did not appear in its entirety,” he wrote.

* * * * * * * * * * *

Columbia Daily Spectator, Volume LVI, Number 118, 18 April 1933

Group Plans Picket Protest For Henderson

Supporters Will Circle Main Library—Howe Bans Mail Distribution Of Campaign Leaflets in Dormitories

While organizations and individuals throughout the city were being enlisted in the campaign for reappointment of Donald Henderson, the Columbia Joint Committee yesterday speeded preparations for bringing the case before the Campus this week.

Preliminary to an outdoor meeting on Thursday at which representatives of Campus groups affiliated with the committee will speak, thirty pickets tomorrow will surround the Main Library, where the offices of Administrative leaders are situated.

Bans Distribution of Leaflet

Distribution of the leaflet entitled “The Henderson Case” which has been circulated on the Campus was temporarily halted yesterday when it was revealed that the University had denied the committee permission to insert the statements in dormitory mail-boxes.

Herbert E. Howe, director of Men’s Residence Halls, told Spectator yesterday that “the University does not allow advertising material in local mail distribution.” He said that he considered the leaflet in that classification.

Committee leaders asserted that the circular on “What Is the Social Problems Club” and the announcements of the Marxist lectures had been recently distributed in dormitory boxes with Mr. Howe’s permission.

To Demonstrate at Sun Dial

As the Association of University Teachers assumed a leading role in organizing city-wide groups for Mr. Henderson’s defense, the Columbia Committee announced that the first of a contemplated series of demonstrations will be held at the Sun Dial in front of South Field. Leaders said yesterday that the meeting will be a “Columbia demonstration limited to Columbia speakers.”

The Association of University Teachers is drawing up a detailed statement on the case, it was made known yesterday, with the intention of submitting it to individuals and groups as the basis of an appeal for widespread support.

Say Henderson Expelled for Beliefs

The Association stated that “it has considerable evidence justifying the opinion that Mr. Henderson was expelled for his political activities and beliefs” and declared that “this is the most important case of violation of academic freedom since the war.”

A committee representing eight college organizations in this city has been formed to aid the protest movement, it was learned yesterday, following a conference at the New School for Social Research last Saturday.

Professor Henry W. L. Dana, who was dismissed from the University during the World War and is now at Harvard, has written to Professor Roswell C. McCrea concerning the Henderson case, it was revealed yesterday, with publication of a copy of the letter by an official of the National Student League.

Text of Letter

Professor Dana wrote:

“Considering the cases of other teachers who have been forced to leave Columbia University in the past (Professors MacDowell, Woodberry, Ware, Peck, Spingarn, Cattell, Beard), not to mention my own name, I cannot help smiling at the unconscious irony in your statement that the case of Mr. Henderson ‘is consistent with long-established University policy.’ “

Members of the Joint Committee indicated yesterday that a strike may be called for next week if ensuing developments “warrant such a move.” They said that demonstrations at colleges throughout the city are being planned.

* * * * * * * * * * *

Columbia Daily Spectator, Volume LVI, Number 119, 19 April 1933

Will Picket Library Today

Henderson Supporters To Stage Three-Hour Demonstration

Student pickets will surround the Main Library at ten o’clock this morning for a three-hour siege of administrative offices to protest against the non-renewal of Donald Henderson’s appointment.

Preparatory to an outdoor demonstration in front of South Field at noon tomorrow, thirty representatives of organizations affiliated with the Columbia Joint Committee will form a cordon encircling the Library where they will maintain their stand until 1 P.M. this afternoon.

15 of Class Sign Petition

Meanwhile, fifteen members of Mr. Henderson’s Economics 4 class yesterday signed a petition, circulated by a student, which terms him a “thoroughly competent instructor and a definite asset to the course.” There were seventeen students present at the class meeting. Twenty-one students are registered in the course, a member of the Economics department said.

This move followed the action of students in Mr. Henderson’s Economics Seminar who last week unanimously voted him “a competent instructor” and said “his analyses of economic theory have been illuminating and intellectually stimulating.”

Announcements Posted on Campus

Posters appeared on the Campus yesterday announcing tomorrow’s demonstration and stating that seven speakers from Columbia organizations would address the meeting. The protesting students will assemble at the Sun Dial. The Joint Committee yesterday released data that a Faculty member and student had compiled, relative to the number of staff members in Columbia College who have not yet received Doctor’s degrees. This investigation was prompted, it was said, by Professor McCrea’s reference to Mr. Henderson’s failure to achieve his Ph.D. during his tenure here.

The survey asserted:

- Of ninety-four Faculty members with the rank of assistant professor or above, twenty-two have not obtained doctor’s degrees.

- Of eighty instructors in Columbia College, fifty are without doctor’s degrees. Of those fifty, thirty-three have served four years or more at Columbia.

- Of the thirty who have received Ph.D.’s, the average time for completion of all requirements was 4.9 years.

- Of thirty-three instructors without doctor’s degrees, the average time elapsed since they received their last degree is 7.6 years.

This data was made public with a statement pointing out that Mr. Henderson is serving his fifth year at Columbia and received his M.A. degree in 1926. Committee leaders said yesterday that from present indications a series of demonstrations, leading to a call for a student strike next week, will be staged. They declared there is a possibility that later meetings would be transferred to the Library steps, despite the University ruling restricting outdoor assemblages to South Field.

* * * * * * * * * * *

Columbia Daily Spectator, Volume LVI, Number 120, 20 April 1933

Group to Stage Protest Meeting

Henderson Adherents to Mass Today — Pickets Surround Library

A mass meeting to protest the University’s failure to renew Donald Henderson’s appointment will be staged at noon today at the Sun Dial in front of South Field.

The demonstration, called by the Columbia Joint Committee which organized in Mr. Henderson’s defense last week, will be addressed by two Faculty members and representatives of Campus groups.

Patrol Library Area

In preparation for the meeting, thirty student pickets yesterday patrolled the area around the Main Library, bearing placards which urged Mr. Henderson’s reappointment. The pickets maintained their stand for three hours, attracting curious groups of spectators and several newspaper photographers.

The Columbia Committee revealed last night that a delegation is being formed to confer with Dr. Butler tomorrow on Mr. Henderson’s status and to present its plea for renewal of his contract.

Cutler Will Speak

Dr. Addison T. Cutler, instructor in economics, and Bernard Stem, lecturer in sociology, will be the faculty speakers at today’s demonstration. Other addresses will be delivered by John Donovan ’31, president of the Social Problems Club; Ruth Reles, of Barnard; John Craze, of the Mathematics Club; Jules Umansky, of the Socialist Club; Edith Goldbloom, of New College and Nathaniel Weyl ’31, now a graduate student.

The picketing continued for three hours yesterday with some students carrying varied placards along the Library Steps, while others formed a cordon encircling the building.

* * * * * * * * * * *

Columbia Daily Spectator, Volume LVI, Number 121, 21 April 1933

Large Crowd Attends Protest For Henderson

150 Hear Addresses by Cutler, Donovan — Term Dismissed Instructor ‘Too Good for Most of People in University’

Agitation for the reinstatement of Donald Henderson continued yesterday when the Columbia Joint Committee staged a demonstration attended by about 150 students at the Sun Dial in front of South Field.

Leading off a series of addresses by members of the Faculty and Student Body, John Donovan ’31, president of the Social Problems Club, declared the Economics instructor was expelled “not because he was too poor a teacher but because he was too good for most of the people in this University.”

Cutler Praises Henderson

Dr. Addison T. Cutler of the Economics Department, one of the two Faculty speakers, stated that “Mr. Henderson has carried out as few educators have done, the maxim that theory and practice should be united.

“It has always been a Columbia tradition,” he declared, “that its teachers should be active in community life. It is now becoming recognized that this means they should be active in their communities along class lines. But if they want reconstruction of the social order they aren’t acceptable to the administration.”

Distribute Protest Postcards

Terming the charge of “academic incompetence” levelled at Mr. Henderson by the University a subterfuge, Dr. Cutler lauded the instructor’s ability and characterized the reasons given for his dismissal by Dean Roswell C. McCrea of the School of Business, as “the thinnest kind of a fictitious peg upon which to hang a hat.”

During the course of the demonstration, members of the Joint Committee distributed postcards addressed to President Butler and bearing the statement: “I, the undersigned student, join the protest against the dismissal of Donald Henderson and demand his reappointment.”

Committee to Meet Butler

A committee delegated by the protest group today will confer with Dr. Butler regarding the non-renewal of Mr. Henderson’s appointment and to urge his reinstatement. Meanwhile, petitions protesting the teacher’s dismissal will be ready for distribution Monday, Donovan stated.

Jules Umansky, of the Socialist Club, also spoke yesterday, asserting that “Mr. Henderson is incompetent from the point of view that he taught what he wasn’t supposed to teach. He is incompetent because he has been teaching young people to think in terms of current problems. He is the only one who has taught this subject.”

* * * * * * * * * * *

Columbia Daily Spectator, Volume LVI, Number 122, 24 April 1933

Group to Meet With Dr. Butler

Henderson Supporters Pick Delegation to Seek Administration Stand

The Administration’s stand regarding the renewal of Donald Henderson’s appointment is expected to receive expression when a special delegation chosen by the Columbia Joint Committee confers today with Dr. Nicholas Murray Butler.

A conference with Dr. Butler was to have taken place last Friday, leaders of the protest group declared, but was postponed until this afternoon “because of some mechanical obstructions.” These, it was stated, were removed with the appointment of a special committee of ten students and one Faculty member and the arrangement with Dr. Butler for a definite appointment.

Delegation Has 11 Members

The delegation which will meet with the president at 3:45 this afternoon is composed of: Bent Andresen ’36; Reginald Call ’33; Dr. Addison T. Cutler, economics instructor; John L. Donovan ’31, president of the Social Problems Club; Edith Goldbloom, of New College; James E. Gorham ’34; Leonard Lazarus, Law School student; Angus MacLachlan ’33; Victor Perlo, graduate student; [a brief biography]; Ruth Relis, of Barnard College and Charles Springmeyer ’33.

National Campaign Planned

Meanwhile, Henderson sympathizers off the Campus moved to obtain widespread backing for their campaign. Invitations have been sent to ten nation-ally-constituted student, teacher and professional groups asking them to a conference for the organization of concerted action on the Henderson to be held Thursday of this week.

The Association of University Teachers has already entered the drive to reinstate Henderson, having sent a telegram to Dr. Butler protesting the dismissal of the instructor.

* * * * * * * * * * *

Columbia Daily Spectator, Volume LVI, Number 124, 26 April 1933

The Case of Donald Henderson

[Spectator Editorial]

What is academic freedom? Obviously, the right of a faculty member to express his convictions, political or social, without the dread that such expression will cost him his position or his chances of promotion. Columbia University, despite Dr. Butler’s reputed statement to the contrary, has violated this code — notably, in the expulsion of outstanding Faculty members during the war hysteria of 1917.

Now comes the cry that the refusal of the University to renew the contract of Donald Henderson is another clear-cut case of disregarding academic freedom. The non-reappointment of Mr. Henderson is said to be a direct result of his economic and political creed. The obvious question is then — Has the University’s action been due to Mr. Henderson’s radical activities?

At Monday’s conference with President Butler, Dr. Addison T. Cutler, member of the Columbia Joint Committee, is quoted as having said:

“Mr. Henderson told me a year ago last Fall that he had been asked to get another job.”

A year ago last Fall would be 1931 — prior to the Reed Harris expulsion, prior to the Kentucky student trip, prior to his arrest at City College. Certainly, his activity in radical circles was: comparatively obscure up until the time when Mr. Henderson says he was told his contract would not be renewed.

From the evidence presented up to the present time, the case of Donald Henderson is not one of clear-cut violation of academic freedom even though his supporters have attempted to make it appear so.

* * * * * * * * * * *

Columbia Daily Spectator, Volume LVI, Number 126, 28 April 1933

From Mr. Henderson

To the Editor of Spectator:

The editorial in Wednesday morning’s Spectator concerning my case raises very sharply one question of fact which I feel requires a statement from me. This point concerns the time when pressure began to be applied for my removal, and the reason for this pressure.

During May 1931 Professor Tugwell informed me that my status as instructor at Columbia was not in question, that the people “downstairs” were satisfied with my work. In October 1931 during the first week of the session, Professor Tugwell. called me into his office and informed me that the situation had radically changed and that I had better look for a position…somewhere else for the following year. It was made clear, however that this was in no sense a case of “firing” but rather a suggestion that I find a position somewhere else if possible.

I immediately raised the question with Professor Tugwell concerning the abrupt change in attitude toward me between May 1931 and October 1931. No definite answer was given by Professor Tugwell beyond a general statement that I was spending too much time in “agitation” and not enough in “scholarly education.”

ln point of fact, what happened between May and was this. As my original statement pointed out I became extensively and publicly active in the Communist movement during the summer and though present members of the editorial board of Spectator may not have been aware of it at that time and know nothing of it now, these activities were attended with considerable publicity.

It is also true that with increased activity and publicity during the past year this pressure has taken on the form of blunt refusal to reappoint. The complaints about my activities were not in any way concealed from me. On the contrary they were several times brought to my attention, and it was well understood in the department that such was the case.

DONALD HENDERSON

* * * * * * * * * * *

Columbia Daily Spectator, Volume LVI, Number 127, 1 May 1933

Groups Rally To Defense Of Henderson

General Committee for Instructor’s Support Is Formed — Speakers at Meeting Call Educational System ‘Sterile’

The campaign for the reinstatement of Donald Henderson assumed nationwide significance over the week-end as the result of three conferences staged by the New York Committee for the instructor’s reappointment.

As the culmination of a week of general organization of the Henderson defense and presentation of the instructor’s case at several city colleges, a meeting was held at the Central Plaza last night at which addresses attacking the University’s failure to renew Mr. Henderson’s appointment were delivered by five speakers, including, for the first time in his own public defense, Mr. Henderson.

200 Attend Protest Meeting

Amid the sounding of a call for a “permanent organization to prevent future violations of academic freedom and to: put forward immediately mass pressure to reinstate Donald Henderson,” the speakers at the meeting, attended by 200 persons, generally condemned the “narrowness, dryness and intellectual sterility,” of the existing educational system.

Mr. Henderson termed Columbia “a liberal university where you may believe anything you please and discuss it freely under academic auspices, provided you hold these beliefs educationally and not agitationally.” Putting into practice personal doctrines which run counter to the “dominant social institutions” will result in “academic suicide,” he said.

Predicts Student Fascist Move

“Both for students and teachers the range of freedom in thought and action is constantly narrowing,” Mr. Henderson stated, predicting the crystallization of a Fascist student movement in America with increasing “tightening of educational lines.”

At an organization meeting Saturday, eight national student, teacher and professional groups, in addition to fifteen college clubs, allied themselves in a “General Committee for the Reinstatement of Donald Henderson.”

* * * * * * * * * * *

Columbia Daily Spectator, Volume LVI, Number 129, 3 May 1933

Henderson to Lecture

Donald Henderson, instructor in economics, will speak on the “Revolutionary Student Movement” at the next of the Social Problems Club’s Marxist Lectures tonight at 8:30 o’clock in Casa Italiana.

* * * * * * * * * * *

Columbia Daily Spectator, Volume LVI, Number 129, 3 May 1933

To Hold Protest At Noon Today

Henderson Supporters Will Mass at Sun Dial For Demonstration

Three radical leaders and ten students will speak at noon today at the second Columbia outdoor mass meeting protesting the University’s failure to renew the appointment of Donald Henderson, instructor in economics.

Characterized by Henderson supporters as “undoubtedly the most important event in the fight,” the protest demonstration to be held at the Sun Dial is expected to draw a city-wide crowd of sympathizers.

Niebuhr to Speak

Speakers at the meeting, according to a statement issued yesterday by the Columbia Joint Committee for the Instructor’s reinstatement will be Dr. Reinhold Niebuhr of Union Theological Seminary, J. B. Matthews of the Fellowship of Reconciliation and Robert W. Dunn of the Labor Research Association. Ten students will also deliver addresses, representing various Campus organizations.

* * * * * * * * * * *

Columbia Daily Spectator, Volume LVI, Number 130, 4 May 1933

Flays Faculty In Marxist Talk

Henderson Says Staff Quit Harris ‘Cold’-Plan Demonstration Today

Charging that American college faculties have failed to give support to student radical movements, Donald Henderson, instructor in economics, declared yesterday evening in one of the Social Problems Club’s series of Marxist Lectures that members of the Columbia teaching staff quit the Reed Harris and other cases “cold” when they thought they might “burn their fingers.”

With a plea for solidarity among student bodies of the nation on issues of importance, Mr. Henderson told a small audience at the Casa Italiana that “it is doubly important to get students of other campuses to come and demonstrate at Columbia.” The most pressing problem facing organized student movements, he said, is the “isolated character” of the individual student bodies.

Students Not Revolutionary

“The total student body in the United States is not revolutionary material,” Mr. Henderson declared, pointing out that the great bulk of present undergraduates came to college in the period when they were justified in looking forward to “a hopeful cultural future,” as well as important jobs on graduation. The depression has not greatly altered the points of view of many students, declared the instructor whose reappointment is being sought by the National Student League.

A fight on academic freedom should not be undertaken only on the basis of its own importance, but should be regarded as “merely the reflection of the broader social situation,” Mr. Henderson declared. Struggles taken up at colleges must be carried on with the intention of calling attention to the revolutionary program as a whole, he added.

A protest demonstration for the reappointment of Mr. Henderson will be held this noon at the Sun Dial in front of South Field, according to supporters, yesterday’s meeting having been postponed on account of rain.

* * * * * * * * * * *

Columbia Daily Spectator, Volume LVI, Number 131, 5 May 1933

500 Attend Demonstration For Henderson

Instructor’s Case Held An Instance of General ‘Academic Repression’ in U. S.

— Sykes Presents Opposition Viewpoint

The case of Donald Henderson is merely a single instance of a general situation of academic repression in this country, it was asserted yesterday by eleven of twelve speakers addressing a demonstration in protest against the failure of the University to renew Mr. Henderson’s appointment.

A crowd of 500 persons, assembled at the Sun Dial, variously expressed, by either cheering or booing, their opinions of the several speakers, among whom was J. B. Matthews, of the Fellowship of Reconciliation. He demanded student support of the Henderson case “as part of an issue we shall be forced in the future to combat in a bigger way, an issue which is now raising its head on the Columbia Campus.”

Tells Group to Organize

“This is the time to awaken, to organize, to stop now the tendency toward academic repression and servility to the prevailing social order,” he declared.

Mr. Henderson’s crime consisted in “functioning effectively in the social order and getting his name in the papers,” according to Robert W. Dunn of the Labor Research Association. “Had he been a respectable liberal and confined himself to harmless academic matters he would have been retained, at full pay, even if he never met his classes,” Mr. Dunn asserted.

Will Picket Today

During the demonstration two committees were organized to picket, commencing at noon today, the home of Dr. Butler and the Columbia University Club rooms. Agitation for Mr. Henderson’s reinstatement will continue Tuesday with another demonstration, followed by a march around the Campus, it was announced to the assembled crowd. An opposition viewpoint was expressed at the meeting by Macrae Sykes ’33, Student Board member who, when asked his opinion of the case, declared “there is a confusion of issues in this case. Academic freedom is not involved in Mr. Henderson’s expulsion. Many teachers at Columbia are expressing to their students the same ideas for which you claim Henderson was fired. These teachers weren’t asked to resign.

“This is no question of academic freedom,” Sykes continued, “but of the right of department heads to hire and fire their subordinates at will.”

* * * * * * * * * * *

Columbia Daily Spectator, Volume LVI, Number 132, 8 May 1933

An Unanswered Question

[Spectator Editorial]

On April 28, Mr. Donald Henderson, in reply to an editorial published two days previous, stated:

- In May, 1931, Professor Rexford C. Tugwell had told Mr. Henderson that his status as an instructor “was not in question.”

- In October of the same year, Mr. Henderson said in his letter, Professor Tugwell “called me into his office and informed me that the situation had radically changed and that I had better look for a position somewhere else for the following year.”

- When Mr. Henderson asked Professor Tugwell the reason “for the abrupt change in attitude toward me between May, 1931, and October, 1931,” the letter declares, “no definite answer was given by Professor Tugwell beyond a general statement that I was spending too much time in ‘agitation’ and not enough in ‘scholarly education.'”

Mr. Henderson’s statements are serious enough to warrant an answer. What happened between the months of May and October, 1931, is a question which silence on the part of Professor Tugwell cannot clear up.

* * * * * * * * * * *

Columbia Daily Spectator, Volume LVI, Number 133, 9 May 1933

Broun, Harris Will Address Mass Meeting

Will Speak Today at Henderson Protest — 26 Prominent Liberals Ask A. A. U. P. tor Inquiry Of Instructor’s Case

Preparations for the third outdoor protest demonstration in behalf of Donald Henderson were completed yesterday as leaders of the Columbia Joint Committee for the instructor’s reappointment made public a letter sent by twenty-six educators, writers and radical leaders, to the American Association of University Professors requesting an investigation of the Henderson case.

Heywood Broun, columnist, Reed Harris, former Spectator editor and Joshua Kunitz, author, in addition to ten student speakers, will deliver addresses in Mr. Henderson’s defense in another protest meeting at noon today at the Sun Dial.

The signers of the communication declare themselves to be “deeply concerned with the issues of academic freedom and free speech” raised in the Henderson case, and request the Association to conduct a “thoroughgoing” investigation.

The full text of the letter follows:

“Professor Walter Wheeler Cook, President,

The American Association of University Professors

Johns Hopkins UniversityDear Sir:

The undersigned individuals are deeply concerned with the issues of academic freedom and free speech raised by the release from Columbia University of Donald Henderson, instructor of economics. Mr. Henderson, who has been an instructor at Columbia for four years, has been notified that he will not be reappointed for 1933-34. The alleged reasons for this refusal to reappoint him are failure to complete work for a Ph.D. degree, and his poor teaching.

“Students and teachers at Columbia and other universities charge that the reasons given by the University for this action are hypocritical and misleading, and that the real reason for his release is his continued radical student and labor activities.

“We believe that the issues involved in Mr. Henderson’s release are of sufficient importance to justify a thoroughgoing inquiry by the American Association of University Professors. Accordingly, we ask you to instigate such an investigation at the earliest possible moment, and to make a report of your findings to the American people.”

The communication was signed by the following: George Soule and Bruce Bliven, of The New Republic; Lewis Gannett, of The New York Herald-Tribune; Freda Kirchway, of The Nation; Alfred Bingham and Selden Rodman, of Common Sense; Harry Elmer Barnes; Sidney Howard; Waldo Frank; Granville Hicks; Professors Broadus Mitchell, Johns Hopkins University; Newton Arvin, Smith College, Robert Morss Lovett and Maynard C. Krueger, University of Chicago, Harry A. Overstreet, C.C. N.Y., Willard Atkins, Edwin Burgum, Margaret Schlauch and Sidney Hook, New York University; Dr. Bernhard J. Stern, Columbia; Norman Thomas, A. J. Muste, Corliss Lamont, Elizabeth Gilman, Paul Blanshard and J. B. Matthews.

* * * * * * * * * * *

Columbia Daily Spectator, Volume LVI, Number 134, 10 May 1933

Broun Asks Student Strike For Henderson

Calls University’s Action ‘Unfair’ — ‘Liberalism’ of Butler Hit by Instructor, Speaking on Own Case — Reed Harris Talks

Heywood Broun, noted columnist, yesterday called upon Columbia students to strike in protest against the University’s “unfair treatment” of Donald Henderson.

Declaring the economics instructor was “fired” solely for his radical activity, Mr. Broun told a crowd of 750 at a protest meeting on 116th Street that they should “come out and fight openly” to affirm the fact that “this University is ours and belongs to nobody else.”

Calls Students’ Judgment Important

“It is a strange thing,” the newspaper man asserted, “that an instructor is incompetent as soon as he becomes interested in radical activities. A remote Administration is not a judge of competence in this matter. The most important thing is what his classes think of Donald Henderson.”

In his second public address on his own case, Mr. Henderson, last speaker at the demonstration, attacked Columbia’s “liberal reputation,” declaring that “the essence of Columbia University’s liberalism is that it permits you freedom of thought as long as you don’t carry your beliefs into action.”

Attacks Liberals’ Policies

The practical application of such doctrines, if they run counter to the “dominant institutions,” causes the University to “distinguish between academic freedom and academic incompetence,” he declared.

“Effective unity of opposing thought and action of this sort,” Mr. Henderson stated, “immediately puts the liberal in a position where he must join the forces of reaction.”

He called upon teachers and students everywhere to “rouse into action and discover the meaning of this liberalism and all the other doctrines that are hung around our necks.”

Reed Harris, former Spectator editor, returning to the University to defend the Faculty member who supported him after his expulsion from Columbia last year, also spoke. He termed Mr. Henderson “one of the most important instructors in America” and called his non-reappointment “a rotten deal for Mr. Henderson and for the students.”

“Education,” he declared, “is a little like beer. It needs ferment to keep it from becoming flat. It needs activity, and teachers like Henderson provide this activity, dispel the unhealthy serenity bred of College Studies and dimly lighted rooms.”

Says Officials Are ‘Hypocrites’

Attacking the Administration’s stand on the case, Harris charged Columbia officials with being “hypocrites.” A charge of “absolute incompetence” and “nincompoopery” was levelled at a majority of Faculty members, some by direct reference, by Joshua Kunitz, writer and Phi Beta Kappa member who received his M.A. and Ph.D. degrees here.

Plans for continuance of agitation were drawn up by Henderson adherents immediately after the protest meeting. Two principal decisions emerged:

Will March by Torchlight

- A torchlight procession around the Campus will take place tonight, commencing at 8:30 o’clock from the Sun Dial. Preliminary to this event, sympathizers will picket the Main Library steps for two hours.

- Tomorrow, a mass picketing of the grounds, conducted by a city-wide group of Henderson supporters, will be held. Dr. Butler’s home will also be picketed.

Other speakers at yesterday’s demonstration included Nathaniel Weyl ’31; Robert Gessner, of the N. Y. U. faculty.

* * * * * * * * * * *

Columbia Daily Spectator, Volume LVI, Number 135, 11 May 1933

Roar, Lion, Roar

[Spectator editorial]

Last night the supporters of the movement to reinstate Donald Henderson held a demonstration on 116th Street. Their intentions were simply to carry on the fight for a cause which they felt was justified.

But the self-styled “intelligent group of Columbia students” determined that the only way to beat the Henderson supporters was by egg-throwing. Dr. Addison T. Cutler, a courageous member of the Faculty, was subjected to the humiliation of having his coat spattered with eggs thrown by a gentleman who dared not come up front and state his case.

This exhibition by a supposedly intelligent group of undergraduates—their complete reversion to howling lynch-law—must leave the-ordinary bystander amazed.

When an alumnus of Columbia College—not a supporter of Mr. Henderson, but one who was merely passing by—got up and pleaded with the undergraduate group to be square and decent, he was greeted with hoots and jeers. It was rowdyism of the worst sort. It was inexcusable.

Students of this calibre will someday be graduated from Columbia College as capable, competent and educated young men.

* * * * * * * * * * *

Columbia Daily Spectator, Volume LVI, Number 136, 12 May 1933

Joint Committee Calls Strike For Henderson

Instructor’s Backers to Stage Walkout Monday – Ask General Student Participation—Will Issue Leaflet on Case Today

A call to all University students to strike Monday in protest against the “continued silence” of the administration regarding the reappointment of Donald Henderson was sounded yesterday by the Columbia Joint Committee for the instructor’s reinstatement.

Declaring that “increasing manifestations of student sympathy and the incontrovertible evidence which has been presented” justify a general walkout, a statement issued yesterday by the Henderson defense group urged students to employ “the most potent weapon of student expression” to fight “this latest attempt to stifle freedom of action.”

Administration Is Silent

“Our campaign has moved forward,” the statement asserted, adding that the administration has been silent “despite the mass of testimony” offered to answer its original statement of the reasons for not reappointing Mr. Henderson.

Complete plans for the strike were speeded overnight with student sympathizers throughout the city voicing support of the move. Pickets to dissuade Columbia students from attending classes Monday will be selected over the weekend, leaders of the protest group announced.

Will Distribute Leaflets

This morning leaflets will be distributed on this and other campuses reviewing the case of Donald Henderson and urging students to participate in the walkout.

It is planned to circulate a petition urging the instructor’s reappointment among members of the teaching departments in an attempt to line up concerted student and Faculty opposition.

From noon till late afternoon yesterday Henderson adherents picketed the Main Library steps and the home of Dr. Nicholas Murray Butler, bearing twenty-foot banners stating “Reappoint Henderson,” and numerous placards.

Many Students Indifferent

Repercussions of the open battle Wednesday night between Henderson supporters and the newly-manifested student opposition sounded from all quarters of the Campus yesterday. While many students hitherto undecided as to their sentiments on the Henderson case have definitely aligned themselves with either opposing or supporting forces as a result of the clash, many expressed continued indifference to the matter.

The opposition ranks, as yet not openly organized, were silent last night regarding plans for further action, but it was considered likely in informed circles that they will intensify their activity and seek to enlarge their numbers, preliminary to a mass counter-move on the day of the walkout.

* * * * * * * * * * *

Columbia Daily Spectator, Volume LVI, Number 137, 15 May 1933

100 to Picket University in Henderson Strike Today

Walkout to Last All Day—

‘To Be Peaceful, Disciplined Meeting,’ Committee Promises—Rivera to Speak

Culminating six weeks of continuous agitation, the supporters of Donald Henderson will go on strike today.

One hundred pickets, drawn from Columbia and other colleges in the city, will patrol all University buildings commencing at 9 o’clock this morning to dissuade students from attending classes in protest against the Administration’s failure to reappoint Mr. Henderson, Henderson sympathizers will enter classrooms to urge students and Faculty to join the protest forces.

Strike to Last Until 5 P.M.

The walkout, continuing until 5 o’clock this afternoon, will be a “disciplined, peaceful affair,” leaders of the Columbia Joint Committee for the economics instructor’s reinstatement promised yesterday. Pickets and striking students have been instructed to “cause no trouble.”

Throughout the day, a continual procession of speakers will mount the Sun Dial to lead protest meetings demanding Mr. Henderson’s reappointment. Included in the list are the following: Diego Rivera, Mexican artist; McAlister Coleman, Socialist leader; Donald Henderson; Paul Blanshard, of the City Affairs Committee; Joseph Freeman, editor of New Masses; Alfred Bingham, son of Senator Hiram Bingham of Connecticut and editor of “Common Sense”; Clarence Hathaway, Communist Party Leader; William Browder; and E. C. Lindeman, of the Social Science Research Council.

Opposition to Demonstrate

Opposition forces could not be reached last night, but it was reporter [that a] counter-demonstration is planned for today. Having organized over the weekend, they are understood to be enlarging their ranks and are expected to offer resistance to pickets and protesting groups for the duration of the walkout.

Friday members of the Joint Committee distributed leaflets urging students to Strike Monday to Reappoint Henderson.” Reviewing the Henderson case thus far, the paper declares

“On Monday students of; Columbia University will once again be called to strike in defense of academic freedom. The time has come when we must resort to that weapon to protect the right of Donald Henderson and instructors after him to carry their beliefs into effective action.”

Leaflet Discusses Case

Discussing the case under four headings, “Why Was Henderson Fired?” “Facts,” “Who Supports Henderson?”, and “Who Opposes Henderson?” the leaflet points out that Mr. Henderson “has been dismissed from his teaching position at Columbia because of his activities in the revolutionary student and labor movement.”

Following a list of the student, teacher and professional groups supporting the economics instructor, the statement of The Joint Committee challenges the opposing student faction, and concludes: “At one and the same time they (the opposition) maintain ‘this is no case of academic freedom and Henderson Should be fired for his Communism! Sweep all radicals Out of Columbia!’ “

“Which is it, ‘gentlemen’ of the opposition,” the leaflet asks, was Henderson fired for radicalism or not? Do you or do you not want Columbia closed to all but goose-steppers? Make up your minds!”

* * * * * * * * * * *

Columbia Daily Spectator, Volume LVI, Number 137, 15 May 1933

Manners

[Spectator editorial]

Today a group of students sincerely devoted to the fight for the reappointment of Donald Henderson will leave their classes and hold an all-day demonstration in front of the Sun Dial. Thus far they have carried on their activities with as much dignity as the opposition would allow. In one specific case they were treated to an adolescent display of rowdyism by a group of students.

We believe that student expression should have every opportunity for full and unrestricted expression, bounded only by certain standards of courtesy and fairness. The Henderson supporters have invited their opponents to speak. They have striven to prevent their meetings from degenerating into brawls upon provocation by a band of egg-throwers.

We hope that the Columbia College students who have made of themselves public examples of irresponsibility will be absent today. By staying away from that which they don’t want to hear, they will restore to themselves some of their fast disappearing dignity.

______________________

Seabrook Farms, N.J. Strike

Daily News (New York, 11 July 1934).

N.Y. Red Run Out as Farm Strike Ends

By Robin Harris (Staff Correspondent of TheNews)

Bridgeton, N.J., July 10.—The sixteen-day strike of the Seabrook Farms workers whose riots and disorders reached a climax in yesterday’s “Bloody Monday” gas bomb attacks was ended today when the strikers overthrew Communistic leadership and threatened to lynch Donald Henderson, Red organizer and former Columbia University economics instructor.

As the resentment of the strikers flamed into anger toward their discredited leader, the authorities slipped Henderson out of town in an automobile, taking him to his bungalow at Vineland, about eight miles from here.

Workers Against Him.

Henderson, whose wife, Eleanor (sic), was one of the twenty-seven strike leaders arrested after yesterday’s riots, found the opinion of the workers solidly against him when he urged them to reject the peace agreement drawn up by Federal Mediator John A. Moffitt.

Shouts of “Run him out of town!” and “Lynch him!” interrupted the pint-sized [According to Henderson’s 1942 Draft registration card his approximate height and weight were 5 foot 10 inches, 140 lbs.] agitator’s flow of oratory when he persisted in addressing the highway mass meeting at which the workers voted 2 to 1 to accept the Moffitt agreement.

Surrounded by deputy sheriffs, Henderson left the meeting and returned to the offices of the Seabrook Farms, where he was greeted with jeers and renewed threats from the workers.

While police officials and members of the farmers’ vigilantes committee strove to mollify the booing crowd, County Detective Albert F. Murray slipped Henderson out of the rear door and departed for Vineland….

The twenty-eight prisoners, twenty-seven seized after the riots yesterday and the other when recognized today, were ordered released by Cumberland County Prosecutor Thomas Tuso after he learned of the strike settlement.

Twenty-one of the prisoners were granted unconditional freedom, while the other seven, including Henderson, his wife, and Vivian Dahl, were continued in $500 bail pending the action of the Grand Jury, which meets in September.

The seven continued in bail were charged with inciting to riot and suspicion of possessing dangerous weapons.

Following the release of the prisoners, Col. H. Norman Schwarzkopf [Fun Fact: father of Herbert Norman Schwarzkopf, Jr. commander of U.S. Central Command who led coalition forces in the Persian Gulf War], head of the New Jersey State Police, announced that he would give the New York Reds twenty-four hours to leave town. Those failing to get out under the deadline will be clamped into jail.

______________________

Grand Jury Probing

The New York Times Sept 11, 1951

“A nationwide search by the Government for Donald Henderson, president of the Food, Tobacco, Agricultural and Allied Workers Union of America, independent, was called off yesterday after the leftist labor leader agreed by telephone to appear here tomorrow before the Federal grand jury investigating subversive activities.

Roy M. Cohn, assistant United States Attorney in charge of the investigation, said that since last Wednesday United States marshals had been trying to locate Mr. Henderson to serve a grand jury subpoena. Late yesterday afternoon, Mr. Henderson called Mr. Cohn from Charleston , S. C., and agreed to appear before the panel.

The grand jury has been questioning labor officials who signed the non-Communist affidavit under the Taft-Harley Law after resigning from the Communist party. …

…Yesterday three other leftist union officials were witnesses before the grand jury. They were James H. Durkis, president of the United Office and Professional Workers of America, independent, who resigned publicly from the Communist party, and Julius Emspak, secretary-treasurer, and James Maties, (or Matles) director of organization, of the United Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers, independent….