This post is the first of two-parts dealing with a married economics couple who taught at the Columbia economics department during the second quarter of the twentieth century, Eveline Mabel Burns and Arthur Robert Burns. [Warning: not Arthur F. Burns!] Both of the Burns felt themselves relatively undervalued by their Columbia colleagues, but the case for Eveline Burns is particularly clear. She was the weaker spouse but in hindsight the stronger economist of the two. This post presents the end-game correspondence for Eveline Burns with respect to the Columbia economics department. She was quite remarkable, someone who can be credited as being the midwife for the birth of the U.S. Social Security System (to use a gendered metaphor for a gendered case). The post closes with a list of her publications and her c.v. that is conclusive (ex post) documentation of just how wrong the Columbia economics department got it in the early 1940s. Brava, Eveline Burns!

____________________________

Department to Eveline Burns

Meet your glass ceiling

Appears to be a carbon copy of a typed copy of the original (no signature, no printed letterhead):

December 9, 1940

Dr. Eveline M. Burns,

2121 Virginia Avenue N.W.,

Washington, D.C.

My dear Dr. Burns:

As you may have heard, Professor McCrea is retiring at the end of the current academic year and the chairmanship of our Department has been passed along to me. After extensive conferences to ascertain the sentiment of our colleagues, I have prepared my first budget letter. In fairness to you as well as to the Department, I feel that I should report to you in very definite terms the attitude of your colleagues toward your future as a member of the staff.

I understand that you are well aware that in previous years opposition has developed to the proposal to advance you from your present position as Lecturer to that of Assistant Professor, an advancement which would carry with it, of course, some intimation of an intention to promote you later to still higher rank and to a permanent career in the Department. I regret to say that in the course of the budget discussions this year it has become apparent that this opposition has not diminished. It is indeed now so substantial that clearly it will be necessary for you to plan your future on the assumption that there is no possibility of advancement to professorial rank or to permanent status in the Faculty of Political Science.

Since I share the admiration that your colleagues in the Department feel for your many admirable qualities and your many impressive achievements, it is not an easy thing to send this message, which, in spite of previous notice, will doubtless cause you pain and disappointment. The plain fact is, however, that even your most enthusiastic friends agree that viewing the situation in all its aspects, you should not be encouraged to believe that your connection can be made more permanent, or that your rank can be advanced. This conclusion has been reached after extended consideration and will not, I feel certain, be modified by further discussion or debate.

In the budget letter you are being recommended for an appointment for the academic year 1941-42 as Lecturer at a stipend of $3,000.

Faithfully yours,

ROBERT M. HAIG

Source: Columbia University Libraries Manuscript Collections. Department of Economics Collection, Box 3 “Budget, 1915-1946/1947”, Folder “Economics Budget, 1940-1941”.

____________________________

Eveline Burns was not amused

Appears to be a carbon copy of a typed copy of the original (no signature, no printed letterhead):

EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT

National Resources Planning Board

Washington, D.C.

January 21, 1941

Professor Robert M. Haig

Faculty of Political Science

Columbia University

New York, N.Y.

My dear Professor Haig:

I have now had an opportunity of reading with more care your letter of December 9th which you handed to me yesterday and I find it is of a nature which obviously calls for a formal acknowledgment from me. Will you therefore please accept this letter as such? Since no reasons are given for the decision you have conveyed to me there is clearly no comment that I can make, ever were any comment appropriate.

I understood you to say that it would be unnecessary for me formally to give you in writing my reasons for being unwilling to accept a full time appointment as lecturer at a stipend of $3,000, and that you would explore the possibilities of a part time arrangement.

There is, however, one phrase in your letter to which I must take exception for the purposes of the record. In the last paragraph but one of your letter you use the words “in spite of previous notice.” I should like to state formally that to the best of my knowledge no such clear statement of the intentions of the faculty has ever been given to me. On the contrary, on each occasion when I have sought a clarification of the situation from the Dean or, at his suggestion, from other members of the faculty, I have always been given to understand that the individual approached was personally sympathetic to my cause and anxious to see my position regularized but that it would take time for this result to be achieved because of certain admitted difficulties which it was hoped would ultimately be removed.

At varying times I have been informed that there were difficulties because of: (a) my sex, (b) the fact that my husband was also on the staff, (c) the personal objections of an individual faculty member; or that it was undesirable to make a formal recommendation at the time because: (a) a recommendation was being made in favor of my husband and it would be unwise to make recommendations for both husband and wife simultaneously, or (b) that there were staff members, junior to myself, whose economic situations were more pressing than mine, or (c) that it would be advisable to wait until my book on British Unemployment Relief was published, or (d) that there was a general shortage of funds in the university.

In these circumstances I feel that it was not unreasonable for me to draw the conclusion, especially in view of the evident validity of the last consideration cited, that the problem was one of “when”, rather than “whether”, my position would be regularized.

The only occasion on which I was given any indication that this might not be the correct interpretation was in December 1938 when Professor McCrea informed me that while the Department was anxious to expand the work in Social Security, there was some disposition on the part of certain members with whom he had talked to feel that they would like to bring in some outside person to head up the work. I immediately offered my resignation to the Dean, on the ground that for me to continue at Columbia University under such circumstances would not be consistent with my standing in my field and the fact that I had for so long been teaching this subject. Moreover, I pointed out that such a decision implied the negation of any hopes of promotion that I might have formed.

At the request of the Dean, I withdrew my resignation until he could call a meeting of the faculty to discuss the question of my future in the University and at his request I furnished him with a list of my professional activities and publications and the names of outstanding experts in my field from whom he could obtain an opinion as to my standing. That meeting was held in January or February of 1939 and I subsequently received a letter from the Dean (which I do not have with me in Washington) informing me that the decision had been “favorable to my cause” or words to that effect. In those circumstances I felt, wrongly as it now appears, that I was justified in not proceeding with my resignation.

I wish to make it very clear that I am calling attention to these facts solely for the purposes of the record. Even had your letter not emphasized the finality of the judgment, I feel that if my colleagues were prepared to reach such a decision after my thirteen years of service without giving me any reasons therefor, it is unrealistic to expect that their attitude would be changed by any reminder of the facts that I have reported. Nor have I any desire to claim, on the grounds of obligation, expressed or implied, a recognition which the faculty is unwilling for other reasons to give me.

May I say how very sincerely I appreciate your frankness and friendliness yesterday in performing a task which I know could not have been a pleasant one for you. I cannot but feel that had my other colleagues displayed an equal candor and courage during the last seven or eight years, the problem of planning my professional and personal life would have been greatly simplified.

Yours very sincerely,

Eveline M. Burns

Source: Columbia University Libraries Manuscript Collections. Department of Economics Collection, Box 3 “Budget, 1915-1946/1947”, Folder “Economics Budget, 1940-1941”.

____________________________

Department to Eveline Burns

Terms of ex-dearment

Appears to be a carbon copy of a typed copy of the original (no signature, no printed letterhead):

February 15, 1941

Dr. Eveline M. Burns,

2121 Virginia Avenue N.W.,

Washington, D.C.

Dear Eve Burns:

This is to report to you that on behalf of the Department I have today sent to the Provost of the University a recommendation that you be appointed Lecturer for the academic year 1941-1942, on a part-time basis, at a stipend of $2,500. This, I understand, conforms to your wishes. This appointment contemplates that you will offer one course and will be available for dissertation, essay, and general Departmental work within the area of your special field. It is understood that the arrangement is for a single year, with no commitment by either of us for the period beyond June, 1942.

I have placed your letter of January 21st in the University file.

I had thought of the New York School of Social Work, but I am told that, for the present at least, there is no opening there that would be attractive to you. There is, however, an opening at Hunter College (which may involve the chairmanship of the Department at $6,000 or more) and I have suggested you name to them.

Faithfully yours,

[unsigned, presumably Robert M. Haig]

Source: Columbia University Libraries Manuscript Collections. Department of Economics Collection, Box 3 “Budget, 1915-1946/1947”, Folder “Economics Budget, 1940-1941”.

____________________________

Eveline Burns to Department

Roger that.

Appears to be a carbon copy of a typed copy of the original (no signature, no printed letterhead):

EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT

National Resources Planning Board

Washington, D.C.

February 27, 1941

Dr. Robert M. Haig

Faculty of Political Science

Columbia University

New York, N.Y.

Dear Mr. Haig:

I wish to thank you for your letter of February 15th stating that you have sent forward a recommendation for my appointment as Lecturer for the academic year 1941-42 on a part-time basis at a stipend of $2,500. I have also noted your statement that the arrangement is for a single year with no commitment for the period beyond June 1942.

Sincerely yours,

Eveline M. Burns

Director of Research, Committee on

Long Range Work and Relief Policies

Source: Columbia University Libraries Manuscript Collections. Department of Economics Collection, Box 3 “Budget, 1915-1946/1947”, Folder “Economics Budget, 1940-1941”.

____________________________

Department to Eveline Burns

Appears to be a carbon copy of a typed copy of the original (appreares to have been dictated) no signature, no printed letterhead):

November 22, 1941

Dr. Eveline M. Burns,

3206 Que [sic] Street, N.W.,

Washington, D.C.

Dear Doctor Burns:

Last January, after you had expressed your unwillingness to accept reappointment as full-time lecturer at $3,000, the part-time arrangement presently in force was made with the understanding that it involved no commitment beyond June, 1942.

In accordance with a decision reached at a conference of members of the department last night, I have included in the budget letter a recommendation that no provision be made for the continuance of your connection with the department beyond the end of the current academic year.

As I send you this communication I am certain that I speak for all of the members of the department in expressing regret for the circumstances which have prevented the realization of some of our hopes and in expressing appreciation of the contribution you have made to our joint product during the period of your association with Columbia.

With renewed assurances of my personal esteem, I am

Faithfully yours,

ROBERT MURRAY HAIG

Source: Columbia University Libraries Manuscript Collections. Department of Economics Collection, Box 2 Folders “Faculty Appointments”.

____________________________

Department to Eveline Burns

Repeat: you quit, you were not fired

December 22, 1941

Dr. Eveline M. Burns,

3206 Q Street N.W.,

Washington D.C.

My dear Dr. Burns:

I beg to acknowledge your letter of December 10th.

My understanding of the course of events in your case, based on the written record and upon my recollection of our conversation on January 20th, 1941, is this:

1) You demanded promotion and expressed an unwillingness to return to us as a full time lecturer at $3,000;

2) You were then told, both orally and in writing, that there was no possibility of advancement to professorial rank or to permanent status in the Faculty of Political Science;

3) Thereupon you suggested a special arrangement for 1941-2, stated, both orally and in writing, to be temporary in character, and to involve no commitment on either side beyond June 30, 1942.

It would seem to be correct to describe what happened as a voluntary withdrawal by you from your position as lecturer because of your dissatisfaction with that status and your unwillingness to continue in it in the face of the University’s inability to promise advancement. It would seem to be incorrect to describe it as a “dismissal”. We decline to regard it as such in our discussions with you and certainly shall not describe it as such in any communications with outsiders who may have an interest in you.

Since, according to my understanding, you were not dismissed, but withdrew, I cannot supply you with the reason for your “dismissal”. You insisted upon promotion. Your colleagues regretfully decided that it was not possible to encourage you to expect promotion to professorial rank and a permanent career in the department.

With respect to the confidential character of the statements at the decisive meeting, I should like to make it clear that, while we agreed not to report each others’ remarks at the meeting, there was no agreement that would preclude any individual who felt so inclined from giving you his own opinion of your qualities in such detail as he might desire.

Yours truly,

ROBERT MURRAY HAIG

Source: Columbia University Libraries Manuscript Collections. Department of Economics Collection, Box 2 Folders “Faculty Appointments”.

____________________________

Department to Eveline Burns

We said: you weren’t fired, you quit

Appears to be a carbon copy of a typed copy of the original (no signature, no printed letterhead):

January 6, 1942

Dr. Eveline M. Burns,

3206 Q Street N.W.,

Washington, D.C.

Dear Dr. Burns:

I beg to acknowledge your letter of December 30th, 1941. [Not found in my files]

I am sorry that my recollection of what occurred at our oral interview on January 20th, 1941 does not substantiate in all particulars the statements you make in this letter. My recollection of what occurred is set forth in my letter of December 22d, 1941.

Yours truly,

ROBERT M. HAIG.

Source: Columbia University Libraries Manuscript Collections. Department of Economics Collection, Box 3 “Budget, 1915-1946/1947”, Folder “Economics Budget, 1940-1941”.

____________________________

Salary Structure of Economics Staff at Columbia and Barnard

1941-42

DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS

The Budget as Adopted for 1941-42

|

Office or Item

|

Incumbent |

1941-1942

ActualAppropriations

|

| McVickar Professor Political Economy |

Robert M. Haig |

$9,000. |

| Professor of Political Economy |

Leo Wolman |

$9,000. |

| Professor of Economic History |

V. G. Simkhovitch |

$9,000. |

| Professor |

Wesley C. Mitchell |

$9,000. |

| Professor |

John Maurice Clark |

$9,000. |

| Professor |

James Waterhouse Angell |

$7,500 |

| Professor |

Carter Goodrich |

$7,500 |

| Professor |

Harold Hotelling |

$7,500 |

| Professor |

Horace Taylor |

$6,500 |

| Assistant Professor |

Arthur R. Burns |

$4,500. |

| Assistant Professor |

Robert L. Carey |

$3,600. |

| Assistant Professor |

Boris M. Stanfield |

$3,600. |

| Assistant Professor |

Joseph Dorfman |

$3,600. |

| Honorary Associate |

Richard T. Ely |

($1,000.) |

| Instructor |

Hubert F. Havlik |

$3,000. |

| Instructor |

C. Lowell Harriss |

$2,400.

($300.) |

| Instructor |

Walt W. Rostow |

$2,400. |

| Instructor |

Courtney C. Brown |

$2,700. |

| Instructor |

Harold Barger |

$3,000. |

| Instructor |

Donald W. O’Connell |

($2,400.) |

| Lecturer |

Carl T. Schmidt |

$3,000. |

| Lecturer (Winter Session) |

Robert Valeur |

($1,500.) |

| Lecturer |

Eveline M. Burns |

$2,500. |

| Lecturer |

Louis M. Hacker |

$3,000. |

| Lecturer |

Michael T. Florinsky |

$2,700. |

| Lecturer |

Abraham Wald |

$2,400.

($600.) |

| Visiting Lecturer |

Arthur F. Burns |

($2,000.)** |

| Departmental appropriation |

|

$800. |

| Assistance |

|

$1,200. |

|

|

|

|

|

$118,400. |

** Chargeable to salary of Prof. Mitchell, absent on leave.

BARNARD COLLEGE:

Economics Budget for 1941-42

| Associate Professor |

Elizabeth F. Baker |

$5,000. |

| Assistant Professor |

Raymond J. Saulnier |

$3,600. |

| Instructor |

Donald B. Marsh |

$2,400. |

| Instructor |

Mirra Komarovsky |

$2,700. |

| Lecturer |

Clara Eliot |

$2,700. |

| Assistant in Economics and Social Science |

Mary M. van Brunt |

$1,000 |

|

|

$17,400. |

Source: Columbia University Libraries Manuscript Collections. Department of Economics Collection, Box 3 “Budget, 1915-1946/1947”, Folders “Economics Budget, 1940-1941” and “Budget Material from July 1941-June 1942”.

____________________________

But don’t cry for Eveline M. Burns

She did very well for herself.

A Festschrift was published in honour of Professor Burns in 1969 under the title: Social Security in International Perspective: Essays in Honor of Eveline M. Burns, Ed. Shirley Jenkins, New York and London, Columbia University Press.

____________________________

Eveline M. Burns’ Publications:

“The French Minimum Wage Act of 1915” in Economica, III, 1923;

“The Economics of Family Endowment” in Economica, V, 1925;

Wages and the State: A Comparative Study of the Problems of State Wage Regulations, London, P. S. King and Son, 1926;

The Economic World: A Survey (with A. R. Burns), London, Oxford University Press, 1927;

“Achievements of the British Pension System” in Old-Age Security: Proceedings of the Second National Conference, New York, American Association of Old-Age Security, 1929;

“Planning and Unemployment” in Socialist Planning and a Socialist Program, Ed. H. W. Laidler, New York, Falcon Press, 1932;

“Misconceptions of European Unemployment Insurance” in Social Security in the United States: 1933, New York, American Association for Social Security, 1933;

“Lessons from British and German Experience” in Social Security in the United States: 1934, New York, American Association for Social Security, 1934;

“Can Social Insurance Provide Social Security?” in Social Security in the United States: 1935, New York, American Association for Social Security, 1935;

“The Lessons of German Experience with Unemployment Relief” in Lectures on Current Economic Problems, Washington, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Graduate School, 1936;

“Basic Principles in Old-Age Security” in Social Security in the United States: 1936, New York, American Association for Social Security, 1936;

Memorandum on “Wall Street Journal” Articles, Washington, Bureau of Research and Statistics (Memorandum No. 3), 1936

Towards Social Security: An Explanation of the Social Security Act and a Survey of the Larger Issues, London, Whittlesey House, and New York, McGraw-Hill, 1936;

“Social Realities versus Technical Obfuscations” in Social Security in the United States: 1937, New York, American Association for Social Security, 1937;

The Arguments for and against the Old-Age Reserve, Washington, Social Security Board, 1938;

“Some Fundamental Consideration in Social Security” in Social Security in the United States: 1940, New York, American Association for Social Security, 1940;

British Unemployment Programs 1920-38 (Report prepared for the Committee on Social Security), Washington, Social Science Research Council, 1941;

Security, Work and Relief Policies (Report of the Committee on Long-Range Work and Relief Policies to the National Resources Planning Board: Eveline M. Burns, Director of Research), Washington, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1942;

“Building for Economic Security—Six Foundation Stones” in The Third Freedom: Freedom from Want, Ed. H. W. Laidler, New York, League for Industrial Democracy, 1943;

“Equal Access to Health” and “Equal Access to Economic Security” in National Resources Development Report for 1943 (Part I), Washington, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1943;

Discussion and Study Outline on Social Security, Washington, National Planning Association (Planning Pamphlets No. 33), 1944;

“Social Security” in Economic Reconstruction, Ed. S. E. Harris, New York, McGraw-Hill, 1945;

“Economic Factors in Family Life” in The Family in the Democratic Society, New York, Columbia University Press, 1949;

“How Much Social Welfare Can America Afford?” in The Social Welfare Forum, 1949, Proceedings of the National Conference of Social Work, New York, Columbia University Press, 1950;

“Social Insurance in Evolution” in Readings in Labor Economics, Ed. F. S. Doody, Cambridge (Mass.), Addison Wesley Press, 1950;

The American Social Security System, Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 2nd edition, 1951;

The Social Security Act Amendments of 1950: An Appendix to The American Social Security System, Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 1951;

“An Expanded Role for Social Work” in Social Work Education in the United States, Ed. E. V. Hollis and A. L. Taylor, New York, Columbia University Press, 1951;

“Fifteen Years under the Social Security Act: An Evaluation” in Current Issues in Social Security, Ed. L. MacDonald, New York University, Institute of Labor Relations and Social Security, 1951;

“The Doctoral Program: Progress and Problems” in Social Work Education in the Post-Master’s Program. No. 1: Guiding Principles, New York, Council on Social Work Education, 1953;

Comments on the Chamber of Commerce Social Security Proposals, Chicago, American Public Welfare Association, 1953;

Private and Social Insurance and the Problem of Social Security, Ottawa, Canadian Welfare Council, 1953;

“Significant Contemporary Issues in the Expansion and Consolidation of Government Social Security Programs” in Economic Security for Americans: An Appraisal of the Progress made from 1900 to 1953, New York, Columbia University Graduate School of Business, 1954;

“The Role of Government in Social Welfare” in The Social Welfare Forum, 1954, Proceedings of the National Conference of Social Work, New York, Columbia University Press, 1954;

“The Financing of Social Welfare” in New Directions in Social Work, New York, Harper, 1954;

America’s Role in International Social Welfare (Editor), New York, Columbia University Press, 1955;

Social Security and Public Policy, New York, McGraw-Hill, 1956;

“Welfare Assistance” in A Report to the Governor of the State of New York and the Mayor of the City of New York, by the New York City Fiscal Relations Committee, New York, The Committee, 1956;

Papers and Proceedings of the Conference on Social Policy and Social Work Education, Arden House, April 1957 (Editor), New York, New York School of Social Work, Columbia University, 1957;

“Social Policy and the Social Work Curriculum” in Objectives of the Social Work Curriculum of the Future, by W. W. Boehm, New York, Council on Social Work Education, 1959;

“The Government’s Role in Child and Family Welfare” in The Nation’s Children, Vol. III: Problems and Prospects, Ed. Eli Ginsberg, New York, Columbia University Press, 1960;

“A Salute to Twenty-Five Years of Social Security” in Social Security: Programs, Problems and Policies, Ed. W. Haber and W. J. Cohen, Homewood (Illinois), R. D. Irwin, 1960;

“Issues in Social Security Financing” in Social Security in the United States: Lectures Presented by the Chancellor’s Committee on the Twenty-fifth Anniversary of the Social Security Act, Berkeley, University of California, Institute of Industrial Relations, 1961;

A Research Program for the Social Security Administration, Washington, U.S. Government Printer, 1961;

“Introduction” in Federal Grants and Public Assistance: A Comparative Study of Policies and Programmes in U.S.A and India, by Saiyid Zafar Hasan, Allahabad, Kitab Mahal, 1963;

“The Functions of Private and of Social Insurance” in Studi sulle assicurazione raccolti in occasione del cinquanterario dell’Istituto Nazionale della Assicurazioni, Ed. A. Giuffre, Milan, 1963;

“The Determinants of Policy” in In Aid of the Unemployed, Ed. J. M. Becker, Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins Press, 1965;

“Social Security in America: The Two Systems—Public and Private” in Labor in a Changing America, Ed. W. Haber, New York, Basic Books, 1966;

“Income Maintenance Policies and Early Retirement” in Technology, Manpower, and Retirement Policy, Ed. J. M. Kreps, Cleveland, World Publishing Co., 1966;

“The Challenge and the Potential of the Future” in Comprehensive Health Services for New York City (Report of the Mayor’s Commission on the Delivery of Personal Health Services), New York, The Commission, 1967;

“Foreword” in Poor Law to Poverty Program, by Samuel Mencher, University of Pittsburgh Press, 1967;

“The Future Course of Public Welfare” in Position Papers and Major Related Data for the Governor’s Conference, Albany (New York), New York State Board of Social Welfare, 1967;

Social Policy and the Health Services: The Choices Ahead, New York, American Public Health Association, 1967;

“Productivity and the Theory of Wages” in London Essays in Economics, Ed. T. E. Gregory and H. Dalton, London, G. Routledge, 1927; republished, Freeport (New York), Books for Libraries Press, 1967;

Children’s Allowances and the Economic Welfare of Children (Editor and Contributor), New York, Citizen’s Committee for Children, 1968;

“Needed Changes in Welfare Programs” in Urban Planning and Social Policy, New York, Basic Books, 1968;

“Social Security in Evolution—Towards What?” in Unions, Management and the Public, New York, Harcourt, Brace and World, 3rdedition, 1968;

“A Commentary on Gunnar Myrdal’s Essay on the Social Sciences and their Impact on Society” in Social Theory and Social Invention, Ed. H. D. Stein, Cleveland, Press of Case Western Reserve University, 1968;

“Welfare Reform and Income Security Policies” in The Social Welfare Forum, 1970, Proceedings of the National Conference on Social Welfare, New York, Columbia University Press, 1970;

“Health Care System” in Encyclopedia of Social Work, New York, National Association of Social Workers, 1971

____________________________

Eveline Mabel Burns

C.V.

Vital information:

Born: Eveline Mabel Richardson on March 16, 1900 in Norwood, London.

Married: Arthur Robert Burns (b. December 2, 1895; d. January 20 1981) of London, 1922.

U.S. Citizenship: 1937.

Died: September 2, 1985 in Newton, Pennsylvania.

Education:

B.Sc. (Econ.), Ph.D. (London), Honorary D.H.L. (Western College; Adelphi; Columbia), Honorary LL.D. (Western Reserve University). Professor Emeritus, Columbia University, since 1967; and Consultant Economist, Community Service Society, New York, since 1971.

Streatham Secondary School, 1913-16; London School of Economics and Political Science, 1916-20; London County Council Tuition Scholarship; B.Sc. (Econ.), 1st Class Honors in Economics, 1920; Ph.D., 1926; Adam Smith Medal for outstanding thesis of the year, 1926.

Positions Held

(1) Normal Full-time Positions

Title of Position. Name of Institution/Organization. Years of Tenure. Compensation

Junior Administrative Officer. Ministry of Labor, London, England. 1917-21. £ 250

Assistant Lecturer, London School of Economics, University of London. 1921-28 (On Leave 1926-8). £ 350

Lecturer, Graduate Department of Economics, Columbia University. 1928-42 (on leave 1940-2). $ 3000-3500

Chief, Economic Security and Health Section, National Resources Planning Board, Washington, D. C. 1940-3. $ 7500

Professor of Social Work and Chairman and Administrative Officer, Doctoral Committee, New York School of Social Work, Columbia University. 1946 to [retired 1967] $ 9500

(2) Special Assignments

London School of Economics. Asst, Editor, Economica, 1922-6.

University of London Social Security Committee. Senior Staff Officer, 1937-9. $6500

Social Science Research Council

National Planning Association, Washington, D. C. Consultant on Social Security, 1943-4. $7000

(3) Visiting Professorships

Anna Howard Shaw Lecturer, Bryn Mawr College, 1944

Visiting Professor, Bryn Mawr College, 1945-6

Visiting Professor, Princeton University, 1951

I have also given short courses or individual lectures at the following institutions:

Department of Economics, University of Chicago

Smith College School for Social Work

Littauer Graduate School of Public Administration, Harvard Univ.

School of Applied Social Sciences, University of Pittsburgh

School of Applied Sciences, Western Reserve University

For several years I have conducted the Advanced Seminar arranged by the Social Security Administration for its senior staff, and have given brief seminars for foreign social security experts brought to this country by the Mutual Security Agency

(4) Consultantships

Consultant, Committee on Economic Security, Washington, 1934-5

Principal Consulting Economist, Social Security Board, 1936-40

Consultant, Social Security Administration, 1948 to date

I have also served as consultant on specific issues to the:

United States Treasury

The Federal Reserve Board

The Works Progress Administration

The New York State Department of Labor

OTHER DISTINCTIONS

Adam Smith Medal for outstanding thesis of the year, 1926

Laura Spelman Rockefeller Fellowship, 1926-8

Guggenheim Fellowship, 1954-5

Florina Lasker Award (“for outstanding contributions in the field of Social Security”), 1960

Honorary Doctorate in Humane Letters, Western College, 1962

Honorary LLD, Western Reserve University, 1963

Honorary Fellow, London School of Economics, 1963

Bronfman Lecturer, American Public Health Assn., 1966

Ittelson Medal (“for contributions to Social planning”), 1968

Honorary Doctorate in Humane Letters, Adelphi University, 1968

Woman of Achievement Award, American Assn. of University Women, 1968

Honorary Doctorate in Humane Letters, Columbia University, 1969

POSITIONS OF CIVIC OR NATIONAL RESPONSIBILITY, MEMBERSHIP OF LEARNED SOCIETIES, ETC.

Member American Economic Association (Member of Executive Ctte, 1951-3 and Vice-President, 1953-4)

National Conference on Social Welfare (Secretary, 1955, First-Vice President, 1956 and President, 1957-58)

American Public Health Association (Vice-President, 1969-70)

Vice-President and President, Consumers’ League of New York, 1935-8

Member and Chairman of various committees, Federal Advisory Council on Employment Security, 1952-70

Member, Legislative Policy Committee, American Public Welfare Assn., 1956-68

Member, Steering Committee, White House Conference on Children, 1959-60

Member, Federal Advisory Committee on Area Redevelopment, Subsequently the National Committee on Regional Economic Development, 1961-69

Member, Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare Hobby’s Advisory Committee on Coverage Extension of the Social Security Act, 1953-4

American Delegate to International Conference on Social Welfare, 1958, and member of Steering Ctte and Vice-Chairman of Commission I

Chairman, Social Security Administration Advisory Committee on Long Range Research, 1961-5

Member, President Johnson’s Task Force on Income Security Policy, 1964

Member of Sub-Committee on Social Policy for Health Care and member of its Executive Committee, N. Y. Academy of Medicine 1964 to date

Member, Mayor Lindsay’s Commission on Delivery of Health Service in New York City, 1967-8

Member, National Council, American Assn. of University Professors 1961-4

Original Source: Eveline Burns Papers. Box 1. University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, Social Welfare History Archives. Minneapolis, MN.

Transcribed and posted on line: Davidann, J. & Klassen, D. (2002). Eveline Mabel Richardson Burns (1900-1985) — Social economist, author, educator and contributor to the development of the Social Security Act of 1935. Social Welfare History Project.

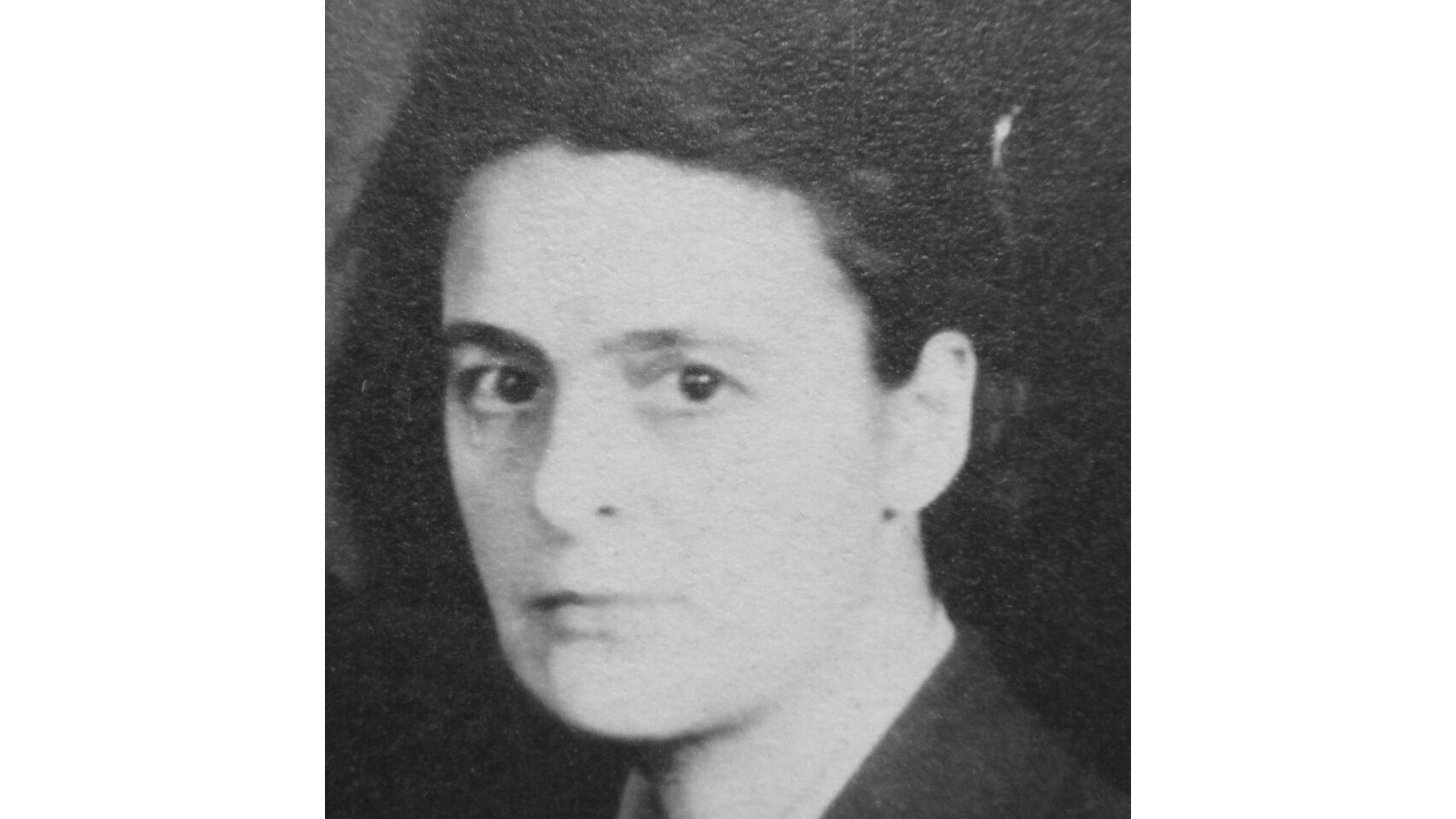

Image: Eveline Mabel Burns. Detail from a departmental photo dated “early 1930’s” in Columbia University Libraries, Manuscript Collections, Columbiana. Department of Economics Collection, Box 9, Folder “Photos”.